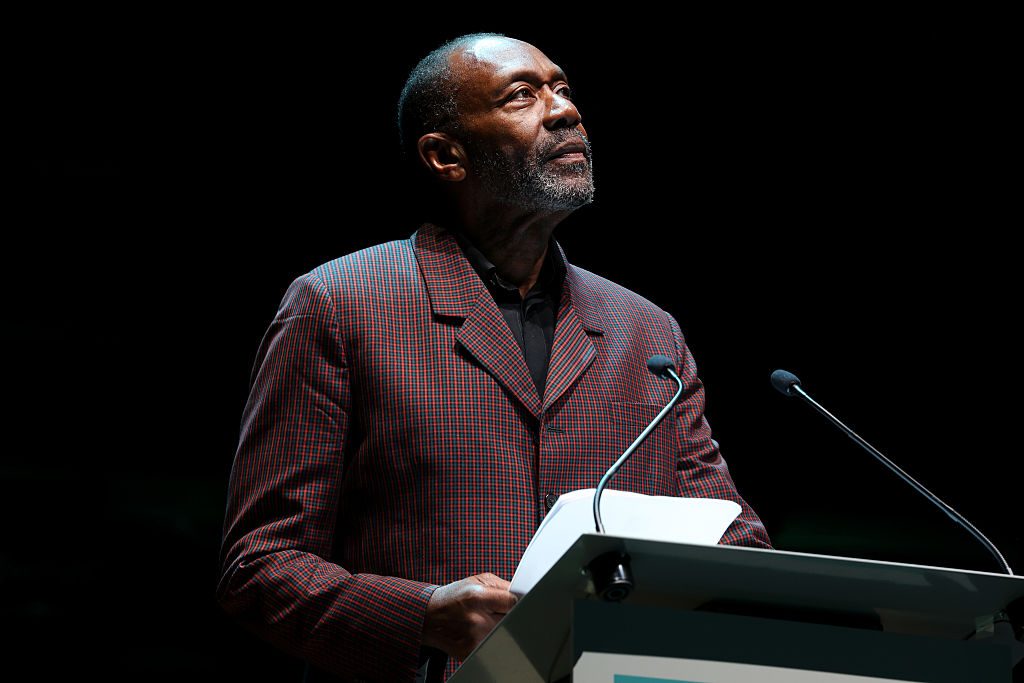

The reparations debate has once again returned to the headlines, with comedian Lenny Henry declaring this week that “all black British people” should receive slavery reparations to the tune of £18 trillion.

At its core, the appeal of reparations is a deeply human one: to compensate for what was unjustly taken. In a society where racism is often treated as the original sin of modern Western civilisation, the prospect of righting historical wrongs naturally stirs the conscience. It is no surprise, then, that activists, politicians, and public figures have returned to this theme for decades.

Yet while reparations may be morally defensible in certain cases, it is naïve to think that payments today for slavery hundreds of years ago will improve race relations and solve lasting disparities. On the contrary, it risks deepening rather than healing the fractures among different communities.

For a start, Britain is a very different country to the US. Slavery and racial oppression have never been enshrined in law in Britain as they have in America. The reparations debate is an issue primarily pertaining to the Americas, and by getting caught up in it we risk importing debates which are irrelevant to modern British life.

On a deeper level, reparations are simple financial transactions. They are an attempt to purchase moral closure. But forgiveness, virtue, and cultural understanding cannot be bought; instead, they must be cultivated. The “eradicate racism through compensation” narrative ignores that racism is cultural, social, and psychological. Money may address some consequences, but it cannot touch beliefs, prejudices, or social structures — ironically, the very forces that progressives often emphasise in these debates.

On top of this dubious premise, what’s even more confusing is how such a scheme would work in practice, given the diversity of black British family histories. Would it be fair for a black Briton of Zimbabwean descent — whose ancestors were never involved in the slave trade — to claim compensation? And how would a Briton of Nigerian descent, whose ancestor may have been a slave trader, fit into such a framework? Would reparations be reserved only for those of direct Caribbean descent? And what of those of mixed West African and Caribbean heritage? These simple questions show that British history is far more complex than the rhetoric around reparations often allows.

When celebrities or activists today call for reparations, they are rarely interested in genuine moral repair and justice. They usually enjoy indulging in identity politics and wearing the cloak of victimhood. Progressives tend to frame history through an oppressor-oppressed binary, where white people are cast as the oppressors and black people as the oppressed. This lens risks essentialising racial identity, reducing complex human stories into fixed categories. In the British context, such a framework flattens history, overlooking how Empire, migration, and class have each shaped the diverse ways black people have come to belong in this country.

Reparations might sometimes be necessary. But acts of reconciliation must arise from genuine generosity and a desire to atone. State-sanctioned financial transactions are hardly the best way to do that. Lenny Henry’s proposal will only lead to greater division.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe