Yesterday’s Senedd by-election in Caerphilly is yet more evidence that Keir Starmer is speedrunning the normal life cycle of a British government. After all, parties have usually been in power much longer than 15 months before they start losing by-elections the way Labour lost yesterday.

This is, after all, no marginal seat. Labour has held it since the creation of the Welsh Assembly in 1999, and its Westminster counterpart has (on varying boundaries) returned a Labour or Labour-Cooperative MP for over a hundred years. No longer: last night, the party limped into a miserable third place, posting just 11% of the vote as Plaid Cymru triumphed.

It would not be fair to allow the Prime Minister to carry all the blame. As so often, there is a strong element of “gradually, then suddenly” to Labour’s collapse in its Welsh heartlands. The party’s vote share has been drifting downward in this seat at both national and devolved elections since the mid-2000s.

But wherever the fingers are pointed, a result like this could presage an absolute catastrophe for Labour in Wales. While Senedd elections have always been much more competitive for other parties — especially the Tories — than is sometimes remembered, Caerphilly is precisely one of those areas upon which Labour’s grip on Welsh politics rests.

More embarrassing still for the party is that this by-election turned into a straight fight between Plaid Cymru, which won 47% of the vote, and Reform UK, which managed 33%. Like the Conservatives in some of their former heartlands, Labour risks finding itself not just defeated but irrelevant.

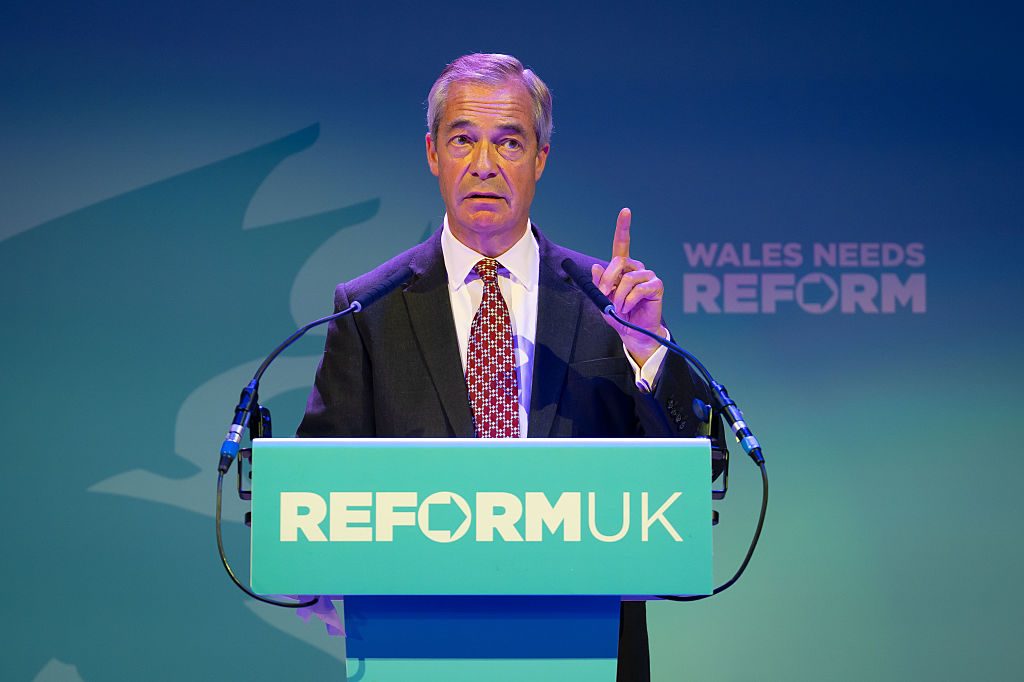

Nigel Farage and co. will obviously be disappointed, despite the strong showing. Victory last night would not have been the first time one of his parties has won representation at Cardiff Bay (Ukip won seven seats in 2016), but it would have been a first for Reform. A voice in the Senedd chamber would have given the party a platform, and forced the media to take seriously the current polling which puts Reform on track for a first-place finish across Wales at the next election.

But Plaid Cymru had a big head start in Caerphilly. Its candidate, Lindsay Whittle, has a high local profile: not only has he twice served as leader of Caerphilly Council and been Plaid’s Westminster candidate in the seat at almost every general election since 1983, but he has previously been an MS for the area (on the regional list) from 2011 to 2016.

Whether or not Whittle manages to hold the seat in the long term likely hinges on Farage’s ability to solve what has for some time been the Right’s biggest structural challenge in Senedd contests. That is, the fact that a large share of Right-leaning voters don’t like the Welsh Parliament and don’t turn out to vote in devolved elections.

The Conservatives, for example, have historically struggled to cement their position as the second party of the Senedd despite being consistently — and comfortably — the second party of Wales at Westminster contests. As with Ukip, a large share of Tory activists are actively hostile to the Welsh Parliament even if the party leadership is not.

In many ways, Caerphilly is a very useful litmus test for this problem. Its Westminster counterpart has historically been relatively good for the Right — for a seat in the Welsh Valleys, that is — and as recently as 2015 the nationalists placed fourth behind both the Tories and Ukip.

If Farage can find a way to get those Right-leaning voters to the polls at the next devolved election, he could shatter the political mold in Cardiff Bay. If he can’t, and devolved elections remain a playground for the more nationalist and Left-wing half of the total Welsh electorate, those tantalizing polls may yet prove an illusion.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe