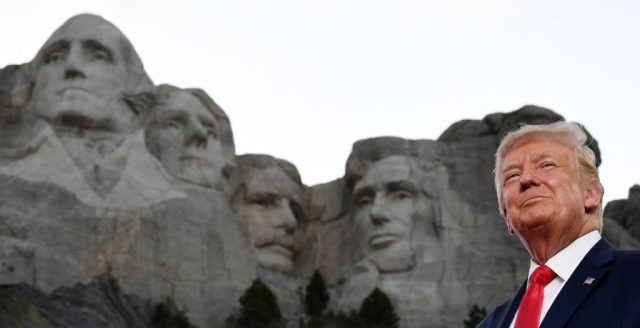

The President marked Independence Day in front of Mount Rushmore in 2020. Photo by SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

From the ancient Redwoods in northern California, to the thunderous roar of Niagara Falls in upstate New York. From the Empire State Building in Midtown Manhattan, to the sandstone buttes rising from the desert floor of Monument Valley, America is a massive, grand, and monumental nation. We think of a monument as a physical structure, but the word derives from the Latin term monumentum, which means a memorial or a tomb — more literally, “a reminder”.

In architecture, monumentalism means power and historical significance. Think of the Egyptian pyramids, which were constructed as elaborate tombs for the pharaohs, and our own Mount Rushmore. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum, the American-born son of Danish immigrants, conceived the idea of using jackhammers and dynamite to carve the faces of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln into the Black Hills of South Dakota. “American art ought to be monumental, in keeping with American life,” Borglum said. He wanted to memorialize America’s greatness in a way that would stand the test of time.

As a political movement, monumentalism is a policy agenda that commemorates people, events, and ideas — it conserves public memory for the next generation. The current moment, more than perhaps any other point in American history, calls for aggressive monumentalism. Since at least the Sixties, progressives have waged a multi-front war on public memory.

They have undermined our system of education, rejected Christianity’s presence in national life, and insisted that America is irredeemably flawed. Supreme Court rulings in 1947 and 1962 effectively ended the centuries-long presence of Christian ideals in public education. Thereafter, activists filled the gap left by Christianity’s absence with leftist ideology. By some estimates, Howard Zinn’s famously controversial A People’s History of the United States (1980) is now used in as many as one-in-four high school history classes. Zinn, a self-described anarchist-socialist, deliberately ignored any historical facts that would have hindered his portrayal of America as a genocidal, imperialist, plutocratic ethnostate. But even if such attacks on cultural memory had already been going on for decades, the year 2020 was the Left’s Year Zero.

After George Floyd’s death, monuments across the country were demolished, defaced, and desecrated. Remember the enthusiastic dismantling of statues of Confederates like General Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. Progressives cheered the attacks, claiming that the monuments were emblematic of “systemic racism.” But the city of Richmond, Virginia created the monuments to reintegrate the nation in the aftermath of a bloody civil war. In destroying them, progressives reopened old (and mostly healed) wounds.

The iconoclasm that erupted in 2020 does not just target memorials to the Confederacy. In Rochester, New York, the seat of the 19th-century anti-slavery movement, a statue of Frederick Douglass, who called the city his home, was toppled. The rioters tried to throw it into the Genesee River. Why? Because when progressives attack American monuments, they aren’t targeting particular memories of history. They are trying to wipe away all of it, and replace national memories with false ones, which they conjure in the public mind by erecting new monuments to the symbols of their revolution. So, as monuments to Thomas Jefferson were felled, statues of George Floyd were raised.

The New York Times’ 1619 Project was an effort to replace the memory of the birth of our nation in 1776 with a fictitious founding in 1619, when the first ship of captured Africans came to our shores. The authors’ goal was to change America by changing how Americans remember the past. Their license to do so depended on humiliating the public, and convincing American citizens that their history had nothing worth remembering.

As the cultural revolutionaries laid waste to public memory, it wasn’t immediately clear how to counteract their efforts. While previous generations of Americans built up the nation in a monumentalist spirit, that spirit has been draining out of public life for decades. Perhaps because, in the years after the end of the Second World War, the past had been sufficiently memorialized: it lived in the hearts of all Americans. But the pride and triumphalism of one generation were replaced by the cynicism of the next. The political Left began to aggressively erase public memory — particularly through revision of school curricula. After that, many Americans no longer agreed upon what, specifically, we ought to remember.

Donald Trump had some ideas. Trump didn’t become a monumentalist once he reached the presidency — he always was one. A teetotaler who seldom appears in public without make-up on his face, Trump is what Russians call a muzhik, a man’s man. He is brash, aggressive, and relishes a challenge. Before the self-proclaimed “builder president” was in a position to commission new monuments, he was building his own. Trump’s buildings in cities like Atlantic City and Las Vegas were maximalist in style and ambition, paying tribute to wealth, luxury, and risk. His first great works transformed the skyline of Manhattan. And, of course, Trump’s skyscrapers were also monuments to Trump himself. They were grand, gold-plated, and lavishly embellished. Before building Trump Tower in Midtown Manhattan, Trump purchased the air rights of a neighbouring property to prevent anyone from building a skyscraper that would block his views. He wanted “soaring picture windows versus tiny ones, an aesthetic consideration that was of the utmost importance”, as he wrote in his book Never Give Up.

But as his political career began in earnest, Trump directed his attention to creating monuments that memorialized America itself: our heroes, our victories, and our history. Trump made tentative monumentalist gestures in his first term. The 1776 Commission, an advisory body tasked by the president with creating strategies for delivering a patriotic education, was a laudable effort to combat the damnatio memoriae embodied by the 1619 Project. As he prepared to hand the presidency to Joe Biden, Trump issued an executive order to establish a “National Garden of American Heroes” consisting of statues of the most notable figures from our history. But when Biden took office, he (or his surrogates) issued an executive order revoking Trump’s plan.

Trump’s second term puts monumentalism at the heart of the agenda. On day one of his second term, Trump signed a memorandum (eventually formalized in an executive order titled “Making Federal Architecture Beautiful Again”) which directs that federal public buildings should respect “classical architectural heritage in order to uplift and beautify public spaces and ennoble the United States and our system of self-government.” Trump embraced a style of architecture that originated in democratic Athens and republican Rome, not necessarily because he prefers order, proportion, and symmetry, but because this particular style is a symbol of America’s founding principles.

The recently-passed “Big Beautiful Bill” sets aside funding to ensure the National Garden of American Heroes will be completed. And several of Trump’s other executive actions demonstrate his commitment to conserving public memory, including one that orders the Secretary of the Interior to take action if “since January 1, 2020, public monuments, memorials, statues, markers, or similar properties within the Department of Interior’s jurisdiction have been removed or changed to perpetuate a false reconstruction of American history, inappropriately minimize the value of certain historical events or figures, or include any other improper partisan ideology.”

Unsurprisingly, Trump’s actions have drawn criticism from progressives, who argue that he is monumentalizing a nation that no longer exists. They point out that the United States had fewer than five million people at its founding, most of them white and Christian. Today, the country’s population is 350 million people of every race and creed, and the critics claim that a coherent, common identity called “American” is impossible to achieve in such a diverse nation.

But the Declaration of Independence exposes such claims as lies. Americans are not defined by skin color, or wealth, or religion, but by life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — unalienable rights which the government must secure. The commonality of American citizens remains rooted in these fundamental principles envisioned and articulated 250 years ago.

In America, new organizations dedicated to this work are springing up. One such group called More Monuments is explicitly devoted to hastening an “American Renaissance” by “commission[ing] landmark monuments and awe-inspiring megastructures that define a new era of American craftsmanship.” On 4 July 2026, the 250th birthday of the nation, More Monuments will unveil a 650-foot tall “Colossus of George Washington.” The public, too, seems to have a renewed appetite for monumentalism: a viral movement to clean the Statue of Liberty has been gaining steam.

The new monumentalism that is unfolding is not limited to the United States. Burgeoning political movements in Europe, represented by parties such as AfD and the Sweden Democrats, are aimed at recovering traditional European culture by remembering the history of distinct European peoples. Unsurprisingly, the iconoclasts working to erase European history read the monumentalist effort to safeguard public memory as a kind of bigotry. It’s nothing of the sort, but they are right to fear it.

The damage wrought by the Left’s attack on memory demands that patriotic writers and artists create new monuments that are worthy of a monumental people. Their task, which we might call a Great Remembering, is to transmit the nation’s traditions and values to future generations, ensuring that young Americans and immigrants to this country can look upon our monuments and read the record we have made. In doing so, we will restore the public’s fading memory of the great lives and historical triumphs that have shaped our way of life.

One hundred years ago, Gutzon Borglum pointed to Mount Rushmore and said: “America will march along that skyline”. What moves the country forward is not the free market or the federal government, but individuals striving after their heroes. Only time will tell if Donald Trump becomes the fifth face carved into Mount Rushmore.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe