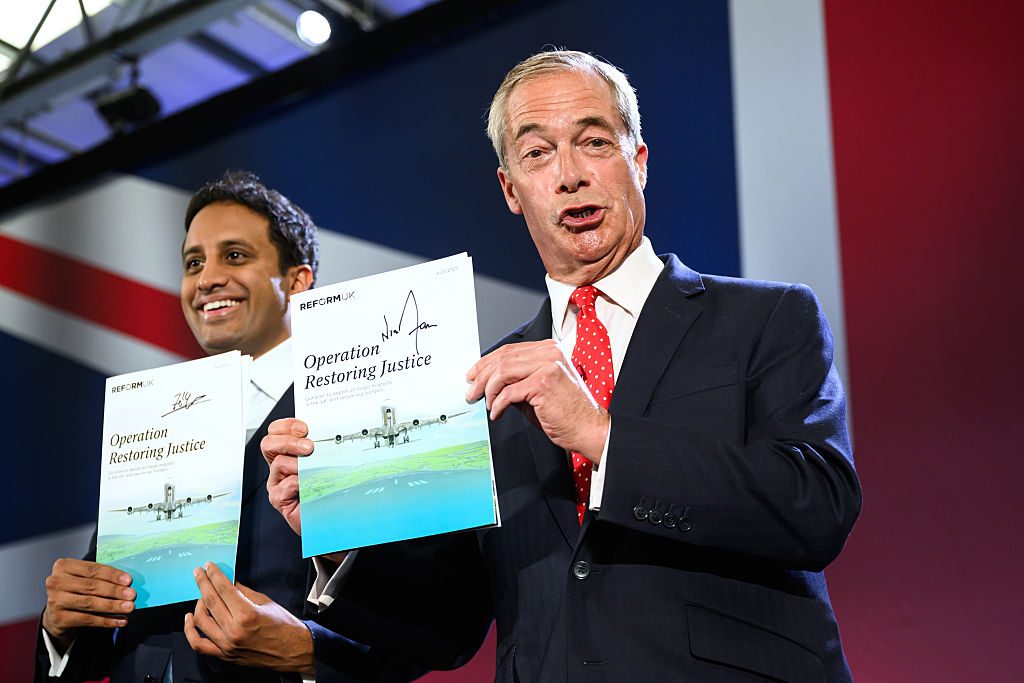

From its inception, Reform UK has always been acutely aware of how best to court media attention. With Nigel Farage at the helm, the party has dispensed bold manifesto promises and policy critiques at every opportunity. Yesterday’s announcement that Reform would deport 600,000 illegal immigrants during its first term in power has undoubtedly added to the momentum.

Speaking in Oxfordshire, Farage pledged to detain and deport any new arrivals via the small-boats pathway, including women and children. He also vowed to leave any international treaties that would prevent this deportation process — most pressingly, the European Convention on Human Rights — and to build immigration accommodation on military bases, as well as using British Overseas Territories as a secondary measure if necessary.

In its current form, the plan rests on two core pillars. The first is the capacity to detain and then house every illegal arrival; the second is the ability to deport these individuals at a rate that is currently unprecedented. Reform has pledged to address this lack of physical infrastructure through the use of “surplus” military bases. The aim is to provide 24,000 detention spaces, representing an increase of nearly 10 times the current detention capacity. The second part of the plan involves an even greater level of scaling, promising to remove 120,000 people per year — 30 times the current deportation level.

While this ambition is worthwhile, the trouble is that Reform will not be able to deliver on such an ambitious plan. Even in the private sector, free from Government inefficiency and bureaucracy, a project of this size would be assumed to cost tens of billions, and would be near-impossible within an 18-month timeframe.

What’s more, these policies will likely collapse on first contact with the Whitehall machine and Britain’s judges. That’s because the legal strategy underpinning the entire deportation process is untenable. Reform appears to be treating the UK’s withdrawal from the European Convention on Human Rights and the repeal of the Human Rights Act as a switch that can be flipped as soon as the party is in power. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. This process would entail years of legislative battles and court challenges from political adversaries, not to mention the intense diplomatic fallout that would result from any successful withdrawal. Even denouncing the UN Convention Against Torture requires a one-year notice period, so the proposal to “disapply” other international treaties would be even more legally tenuous and time-consuming.

Reform should instead focus on the factors that can be controlled immediately, without the need for legal wrangling. For instance, tariffs could be imposed on French goods until the government takes stronger measures to prevent illegal Channel crossings. Additionally, domestic reforms are needed to eliminate the financial incentives that fuel illegal immigration, while providing immediate measures to address the issue before a major legislative overhaul can take effect.

Unfortunately, Reform is operating under the misguided belief that this can be finalised swiftly upon arrival in Number 10. In doing so, Farage is fundamentally underestimating the regulatory quagmire that has damned all recent attempts at controlling immigration. So while this new proposal will go some way towards satiating the desires of those angry at Labour’s inaction, Reform may soon find itself in the same position.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe