In the first hour of Phillip Schofield’s Cast Away on Channel 5 — during which the erstwhile presenter is stranded alone on a desert island — the words of the Victorian essayist Thomas Carlyle came to mind. “What on Earth is the use of a wretched mortal’s vomiting up all his interior crudities, dubitations, and spiritual agonising belly-aches, into the view of the public, and howling tragically, ‘See!’ Let him, in the Devil’s name, pass them, by the downward or other methods, in his own water-closet, and say nothing whatever!”

Schofield is the master of both the mirthless laugh (cracking up when nothing remotely amusing has been said) and the performative sob (crying on cue, and then over to Gino in the kitchen). His four-decade TV career involved introducing other people and nodding goodbye to them, like a chatty doorman. As a personality on his own, he is just very, very, very dull. His persona was always squeaky and sexless, like a bright 11-year-old. True to form, the actual survival stuff in episode one — supposedly the bread and butter of this format — was excruciatingly dull too.

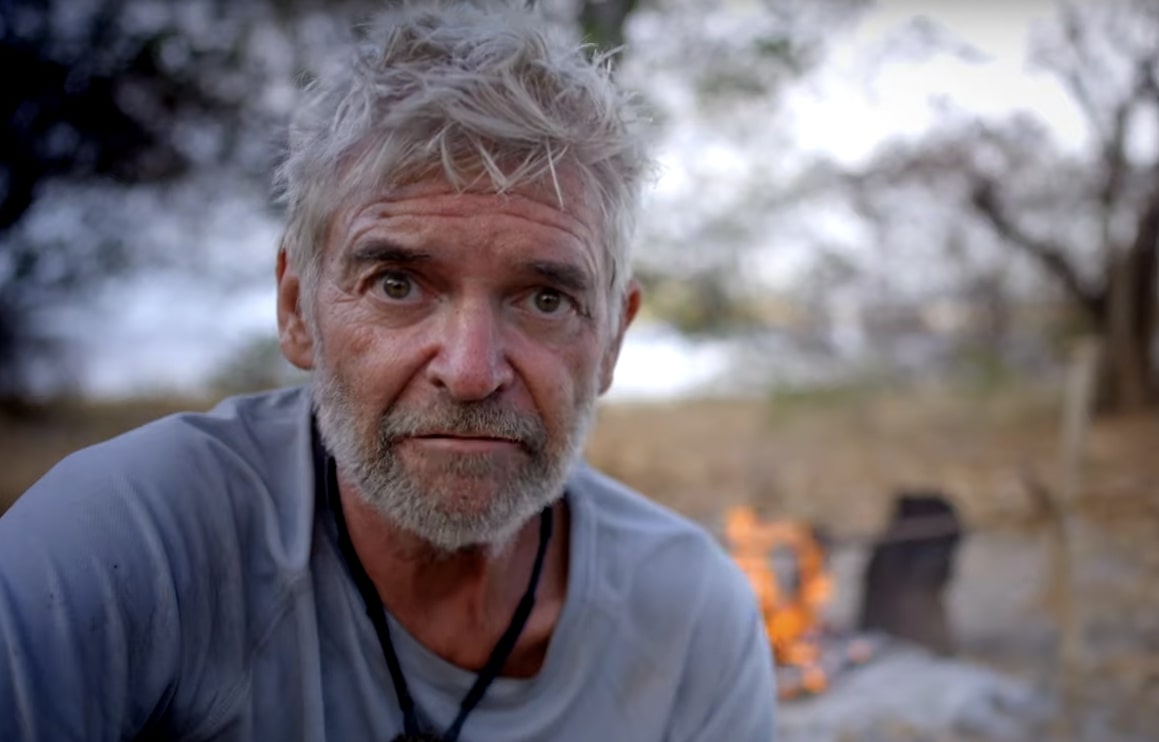

He has returned to TV on the assumption that anybody cares. And he has assumed correctly. Because here he is, and here we are.

The isolation of a desert island never really clicks for him or for us, because you’re never alone with an ego that size. “I never wanted to be famous,” he claims at one point, seeming to forget that he’s in the Indian Ocean trying to shake unripe mangos from a high branch for the diversion of the viewing public. He is weirdly reminiscent, in his slow telling of obvious points and pointless stories, of Beverley from Abigail’s Party.

“You look at the things that hurt you the most on your phone,” he says at one point. Well yes, you probably do, if there’s something terribly wrong with you.

There is a hell of a lot of self-examination in Cast Away, but this — as is so often the case — does not lead to an equivalent amount of self-knowledge. I know what his problem is after five minutes; all that surface chummy amiability, the frequent mock-laughter at his own bitter little asides. It’s all avoidance.

“For some reason I can’t sit completely still,” he says at one point, very tellingly, and slightly later, “I cannot stand having sticky hands”. You hardly have to be Sigmund Freud. He is disconnected from himself, from the world and from other people, but overcompensates by talking at length about how connected he is, as disconnected people will do. He seems unaware that what really sunk him with ITV wasn’t the “unwise” affair, but the subsequent, and protracted, period of lying to them about it.

The lure of being “lovely Phillip Schofield” still remains overpoweringly strong. It is very clear that he doesn’t feel that he exists except when on television. The thought of just not saying anything, keeping his family and private life private, and retiring in enviable luxury never seems to have occurred to him. Because he has to be seen. He has to return.

Personally, I cannot imagine what would make a person describe their own closeness to suicide, not to a close friend or relative or a counsellor or a therapist or a priest, but to millions of strangers through the medium of Channel 5. It’s hard not to feel sympathy for Schofield, because he is a lost soul. Just not for the reasons he thinks he is.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe