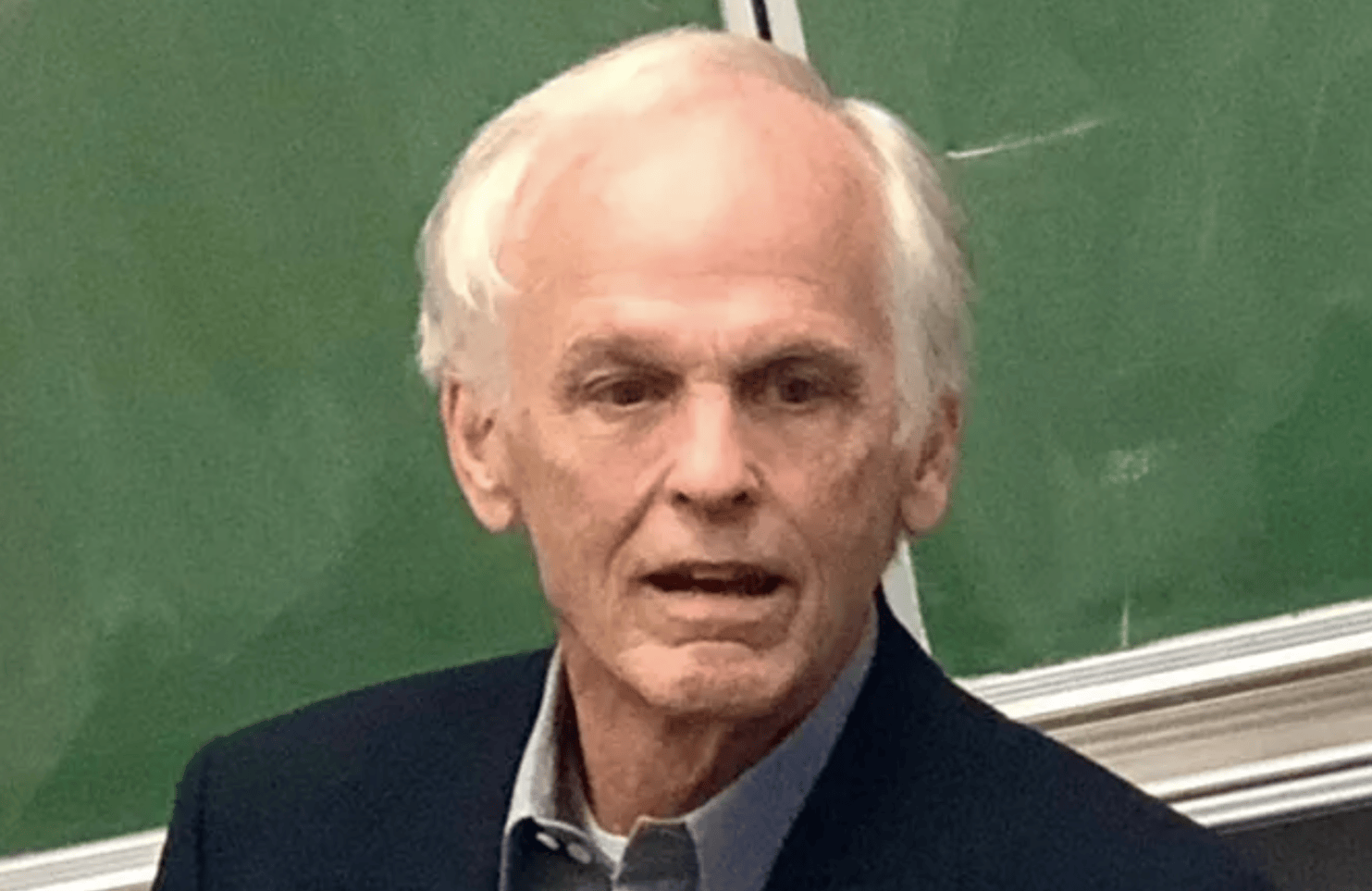

Perry Link’s op-ed in Thursday’s Wall Street Journal gives the reader an uncomfortable sense of déjà vu. Professor Link, a long-tenured comparative literature professor at the University of California, Riverside (UCR), is the latest in a long train of academics subjected to years of quasi-legal harassment at the hands of university administrators for an act of ideological heresy.

Link’s specific offence was to suggest in a private email to fellow members of a faculty search committee that the committee might be unfairly exaggerating one candidate’s fitness for the job and elevating him over others due to his skin colour. Far from being guilty of “discrimination,” as UCR’s chancellor alleged, Link was simply observing a phenomenon that many who have served on university search committees will unfortunately recognise, even if they’ve lacked his courage to call it out.

Two aspects of Link’s ensuing court martial are by now painfully familiar: university authorities’ refusal until very late in the process to identify the exact statement or words of Link’s that were being investigated, and the fact that after a year of sound and fury — threats of pay-cuts, loss of tenure, and termination — Link was found to have done nothing wrong.

Link’s treatment is particularly egregious considering his background which, likely out of modesty, he omits from his op-ed. Not only is Link an 79-year-old distinguished professor with decades of service to his university, as well as to Princeton and UCLA, but he helped facilitate the 1989 escape of Chinese pro-democracy dissident Fang Lizhi to the United States, away from the near certainty of long-term political imprisonment.

In 2001, Link also edited The Tiananmen Papers, a book of translated primary-source documents on the Chinese Communist Party’s decision to use military force against its citizens in the Tiananmen Square Massacre — vital scholarship in the West’s continuing fight to expose CCP human rights violations. Professor Link is therefore something that few current American academics can claim to be: a true American hero.

From his treatment by UC Riverside, one could be forgiven for assuming that Link was a new hire with few accomplishments to his name. But in the context of similar cases of the long-term harassment of heretical professors by administrators (and student mobs, allowed by administrators) — Nicholas and Erika Christakis at Yale, Roland Fryer at Harvard, Brett Weinstein at Evergreen State, and Peter Boghossian at Portland State, to name a few — Link’s treatment starts to look dispiritingly normal.

Link’s experience is reminiscent of Boghossian’s. After the Portland State assistant professor of philosophy participated in the “Grievance Studies Affair,” writing several “intentionally deranged” articles and submitting them to peer-reviewed journals in a range of humanities disciplines in a (successful) effort to show how far academic publishing standards have fallen, he was investigated by Portland State’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), for “experimenting on human subjects.”

That research ethics panel never demonstrated how Boghossian had run any sort of “experiment” which the IRB would be responsible for monitoring, but found him guilty nonetheless. Boghossian would endure years of harassment from both students and faculty, with the threat of denial of tenure. In the end, Boghossian quit.

It’s easier for witch-hunters to justify their actions to others (and to themselves) if they aren’t constantly confronted with evidence of their own injustice. This is the reason why so many campus inquisitions have consisted of harassing or bullying faculty members into resigning of their own volition, rather than firing them. With faculty disciplinary bodies being of virtually a single ideological mind, revoking heretical professors’ tenure is not as difficult as some on the outside might assume. What is difficult is living with the shame of knowing that you railroaded an innocent man or woman. Far easier to tell yourself that in the normal course of “due process,” a colleague simply chose to resign because they didn’t need the aggravation.

It is a credit to Professor Link for sharing his story. Because it may be that our best hope for protecting other academics from Professor Link’s fate is public pressure — pressure from university donors, alumni, and the broader public — to return our universities to being tolerant forums of open inquiry, not seminaries of ideological orthodoxy.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe