There have been many bizarre excuses for poor behaviour over the years. Consider Prince Andrew’s inability to sweat, Dominic Cummings’s trip to Barnard Castle for an eye test, and Woody Harrelson punching a photographer because he thought he was a zombie.

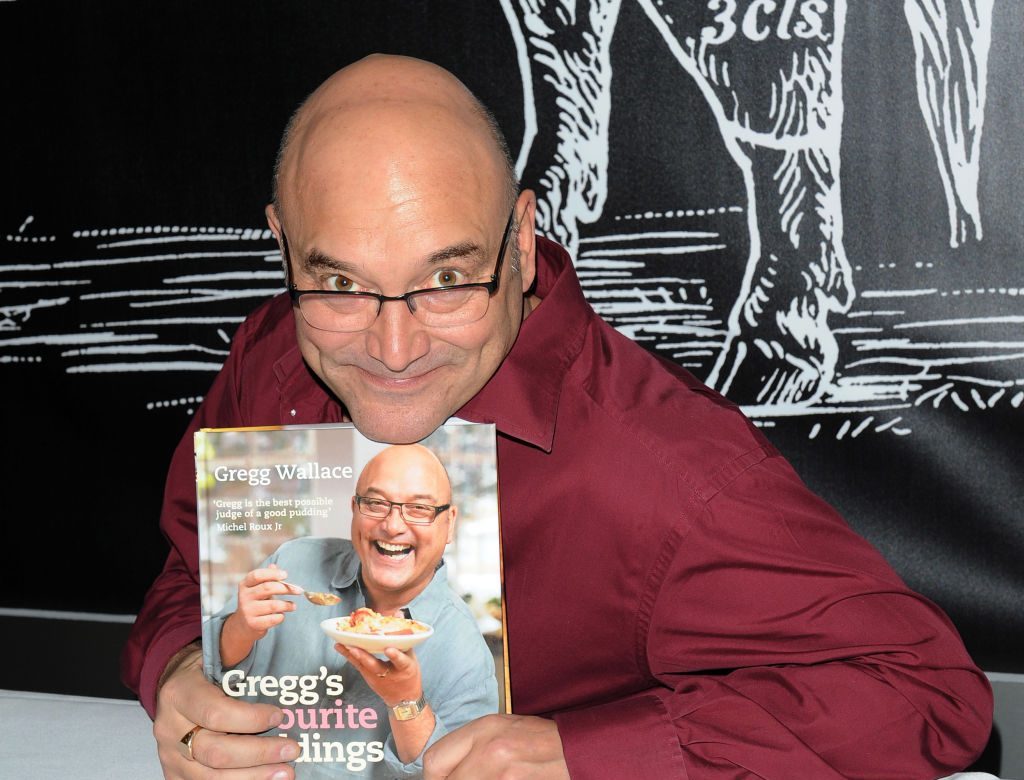

We can now add to this list “cheeky greengrocer” Gregg Wallace, who was this week sacked from MasterChef after more than 50 people came forward with allegations of inappropriate sexual comments and behaviour.

Friends of Wallace have claimed these allegations are due to a misunderstanding of his autism, such as his “oddity of filters and boundaries” and his “inability to wear underwear due to his hypersensitivity to labels and tight clothing”.

The presenter has been quick to position himself as the victim, and use his condition as some sort of defence for his misconduct. Wallace posted on Instagram that his “[neurodivergent] authenticity was part of the brand”, but in our “sanitised world, that same personality is seen as a problem”. There are reports he plans to sue the BBC for discrimination, as he claims his “autism was suspected and discussed […] yet nothing was done to investigate [his] disability or protect [him] from this dangerous environment”.

Wallace’s desperate attempt to reclaim some sort of credibility would be laughable if the same playbook hadn’t also been used in the most serious and criminal cases. There have been multiple cases of paedophiles blaming their ADHD, autism or depression for their sick obsessions. A teenage boy who stabbed a girl in the neck after a row over a teddy bear tried to deny murder, claiming his ADHD affected his ability to exercise self-control, while other criminals have tried to blame their actions on “autistic meltdowns”.

While Wallace is using his autism as an answer, it is really a question. Is autism, and neurodivergence in general, a superpower or a disability? How, as a society, do we know how to deal with autism, and the question of agency, when the spectrum for diagnosis has become so very wide? How do we reconcile the fact that celebrities such as Wallace or Greta Thunberg technically have the same label as someone who soils themselves and requires round-the-clock care?

Wallace may hope that we forgive outsiders like him, yet our conceptualisation of autism is becoming increasingly unclear. On the one hand, we have romanticised neurodiversity as mere eccentricity, or a collection of extraordinary abilities (think the Rain Man stereotype, or Silicon Valley “tech wizard”). We have reframed conditions such as autism as merely a difference in neurological functioning rather than a life-limiting disability. In doing so, we have moved away from the medical model — which sees autism as a checklist of dysfunctions and deficits — to a social model based on identity and a “different way of being”.

The MasterChef presenter’s comments are infuriating precisely because they reveal the uncomfortable duality and contradictions inside this messy spectrum: autism is still a disability, and sometimes autistic people need protection from themselves. He is still egregiously wrong to try and use his autism as a scapegoat. Yet in doing so, he reminds us how, because the definition of autism is ever-expanding, people can use their diagnosis to excuse their behaviour rather than using their behaviour to excuse the diagnosis.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe