I sometimes joke about how we’re never going to get pre-digital cultures and social structures back, unless someone figures out how to unplug the internet. It always seems absurd, as I write it. But today the web services provider Cloudflare almost managed to do just that.

Ironically, the whole point of Cloudflare is providing stability to smaller websites, by smoothing out spikes in online traffic for its customers so they don’t go offline. Even more ironically, the outage was apparently caused by an unusual spike in traffic. With its outage, whole chunks of the internet just disappeared, including popular websites such as X, Spotify, ChatGPT, gambling platform Bet365, and the gay dating app Grindr.

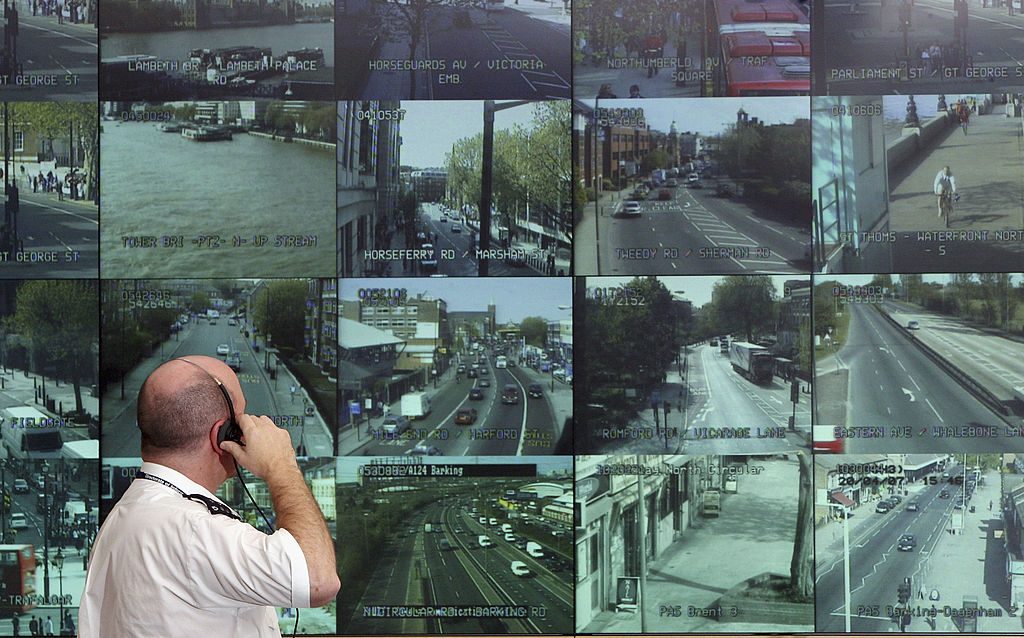

The outage comes scarcely a month after an Amazon Web Services bug similarly caused havoc across the internet. This in turn followed not long after a power cut downed electrical services across the whole Iberian peninsula for almost a full day in April. Such invisible networks — first the electrical one, and then more recently the digital one — are generally taken more or less for granted, woven as they are into the ordinary fabric of life. Great swathes of the economy — not to mention ordinary cultural, social, and political life — depend on them. And it’s no longer just preppers who worry about it all going away: network experts are also beginning to raise concerns about how fragile everything is.

For one thing, the physical infrastructure beneath our digital layer is potentially vulnerable, from data centres to undersea cables. Such large-scale hardware may indeed already be a target for what the military consultant David Kilcullen calls “liminal warfare”, which is to say grey-zone hostilities. For example, last year a Chinese ship caused a diplomatic incident when it was found dragging its anchor, apparently intending to sever undersea cables in the Baltic.

Add to this the complex and sometimes unpredictable interdependencies of digital systems, and the pervasiveness of intermediary services such as Cloudflare, and it begins to feel a bit like the banking system in 2008: unnervingly wobbly, and also too big to fail.

Cloudflare’s outage wasn’t hostile actors — at least as far as reports can make out so far. Services are now coming back online, but a pervasive sense of vulnerability lingers. Should we worry, with those experts, that too much of what we consider to be “the modern world” would simply disappear? Especially since the pandemic, the developed world has shifted decisively to a digital-first culture. Much of politics now travels via the internet, including on X and Trump’s Truth Social — which was also hit today. So does huge amounts of commerce: PayPal was affected, as was the second-hand trading site Vinted.

What would happen if the internet ended up more comprehensively disabled, and for longer? It’s no longer possible in many places to book a doctor’s appointment in person, or to see a bank manager in-branch. Great swathes of the middle class re-organised their households — and in some cases moved house — post-Covid, on the assumption that we’d all now be able to work remotely, at least in part, forever. Local newspapers have long since been replaced by social media. Physical stores have given way to online shopping. More recently, we’ve even begun to outsource thinking to the internet: teachers report that their students routinely appear to hand their assignments to ChatGPT. How long would it take us to re-adapt? Could we?

Of course, one service isn’t the whole internet. But the idea that someone could actually unplug the internet one day feels less absurd than it did a year ago. And in light of this, it’s unsettling to consider how much local resilience we’ve traded away, in exchange for app-based convenience.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe