Our passport to freedom Photo: Dominic Lipinski – WPA Pool/Getty

Britain’s pundits and experts (many moonlight as both) haven’t covered themselves in glory with their predictions throughout the pandemic. We have heard assertions that the UK had already reached herd immunity so there’d be no cases left by Christmas; forecasts that the infection fatality rate would be as low as 1 in 10,000; expectations from MPs that the virus would just go away on its own due to the Gompertz curve; or that there would never be a Covid vaccine. All of these were completely wrong, and all helped sow confusion, delaying decisions and making the virus harder to tackle in the long run.

This cacophony of almost random forecasts isn’t unique to public commentary on viruses – almost any area of national debate is drowning in confident predictions, very few of which have much value. Most of those you read suffer from one of two problems: the forecaster probably isn’t telling you what they really think, and even if they were, what they think might not be any good.

Accuracy, even among professional forecasters like intelligence analysts, has often been a target rather than an achievement. So anyone trying to work out who to listen to in order to understand the future always had their work cut out for them.

That’s why in 2011 the US Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity agency, IARPA, invested in a massive forecasting competition to try and make concrete improvements. Teams would compete to forecast hundreds of topics over four years, from a range of subjects in different countries, with the winning strategies studied and shared with the wider intelligence world.

The bestselling book Superforecasting went on to describe the techniques used by the winning team (of which I was a member) in that competition. We didn’t get everything right, but we learned that it’s possible to do a lot better than foreign policy experts by moving away from the traditional methods employed.

There were three key structural lessons from the competition:

- Keep score

- Identify the best forecasters

- Work as a team

The most important item on this list is keep score. Most forecasts that we come across in the media are made by in-house pundits or people rung up by television stations or newspapers for a quote, and these aren’t scored – there’s no penalty for being wrong most of the time. Old articles are rarely revisited and if they are, the pundit can normally wave away criticism and continue along the same line. Some pundits have made a career out of political analysis despite consistently being wrong in their predictions.

If there’s no reward for getting things right, then accuracy will drop down the list of incentives behind the forecasts. Instead pundits will say what they think will cheer people up, what will promote their career via wacky, attention-grabbing predictions, what shows loyalty to their friends or signals political values and ideals to others — or any of the million other reasons someone might predict something without actually expecting it to happen.

It’s not just that pundits and others in the public eye are bad at predicting, they’re mostly not even trying to. And these predictions can influence politicians and decision makers.

The way to build a successful forecasting system is to reward people for accurate forecasts and disincentivise bad ones. Just that little step, of keeping score and letting everyone know at the start that what they say will matter, immediately changes everything. Now when someone is tempted to predict great success for a project led by their pal, they might think about how embarrassed they’ll be if it goes wrong, and drop their confidence.

Once people are actually trying to predict accurately, you can move on to step two — feedback. Scorekeeping doesn’t just incentivise people to be honest, it also gives them the opportunity to improve. Once you know what you’ve got right and got wrong, you can go back and review. As forecasts resolve, people tend to get better calibrated – that is, there develops a closer relationship between their confidence in their forecast and the outcome.

And once you have a regular run of forecasts, you can take one of the most important steps — stop listening to people who can’t or won’t predict accurately, and pay attention to the most accurate team members, the “superforecasters”.

One of our most striking findings was that the ability to forecast is a skill in itself, independent from subject matter knowledge. Successful forecasters aren’t perfect, of course, but a good track record of predictions is a strong indicator of future performance. And with these skills, superforecasters work for banks, governments and other organisations providing probability estimates for all kinds of risks as well as training analysts in forecasting.

In a system where forecasters are punished for getting it wrong and rewarded for getting it right, the most accurate people float to the top, and when they work together on a team, they become even more accurate.

The forecasts

Last week we gathered a small group of well-calibrated forecasters with good track records to look at the UK’s pandemic outlook over the next few months. With Britain facing both the worst period of the crisis but also an exit strategy with the vaccine roll-out, “when will this end?” is the most urgent question everyone is asking right now.

We can’t promise clairvoyance, but we made the best use of our team’s skills and produced the following set of estimates on three topics:

- How bad the daily death toll will get

- How many vaccines we’ll have administered at the end of February

- When daily deaths will first fall below 100

Superforecasters cannot predict exactly when the pandemic will be over, but these three questions act as proxies for the questions of how bad it will get, how soon an individual is likely to get a vaccine, and when the pandemic will recede. A double-digit daily death toll does not mean the end of the nightmare, but with large-scale vaccinations taking place it will certainly mean is in sight.

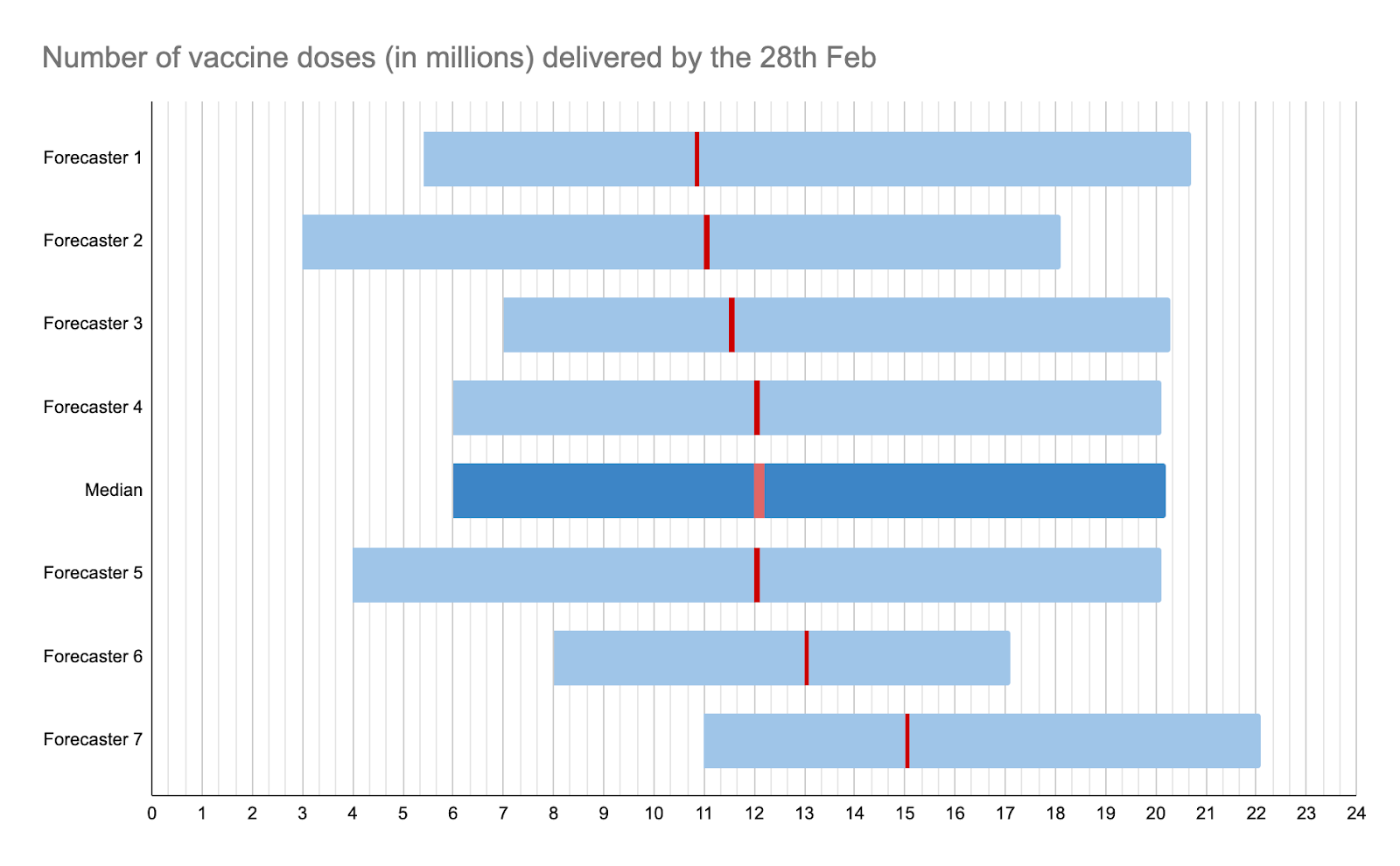

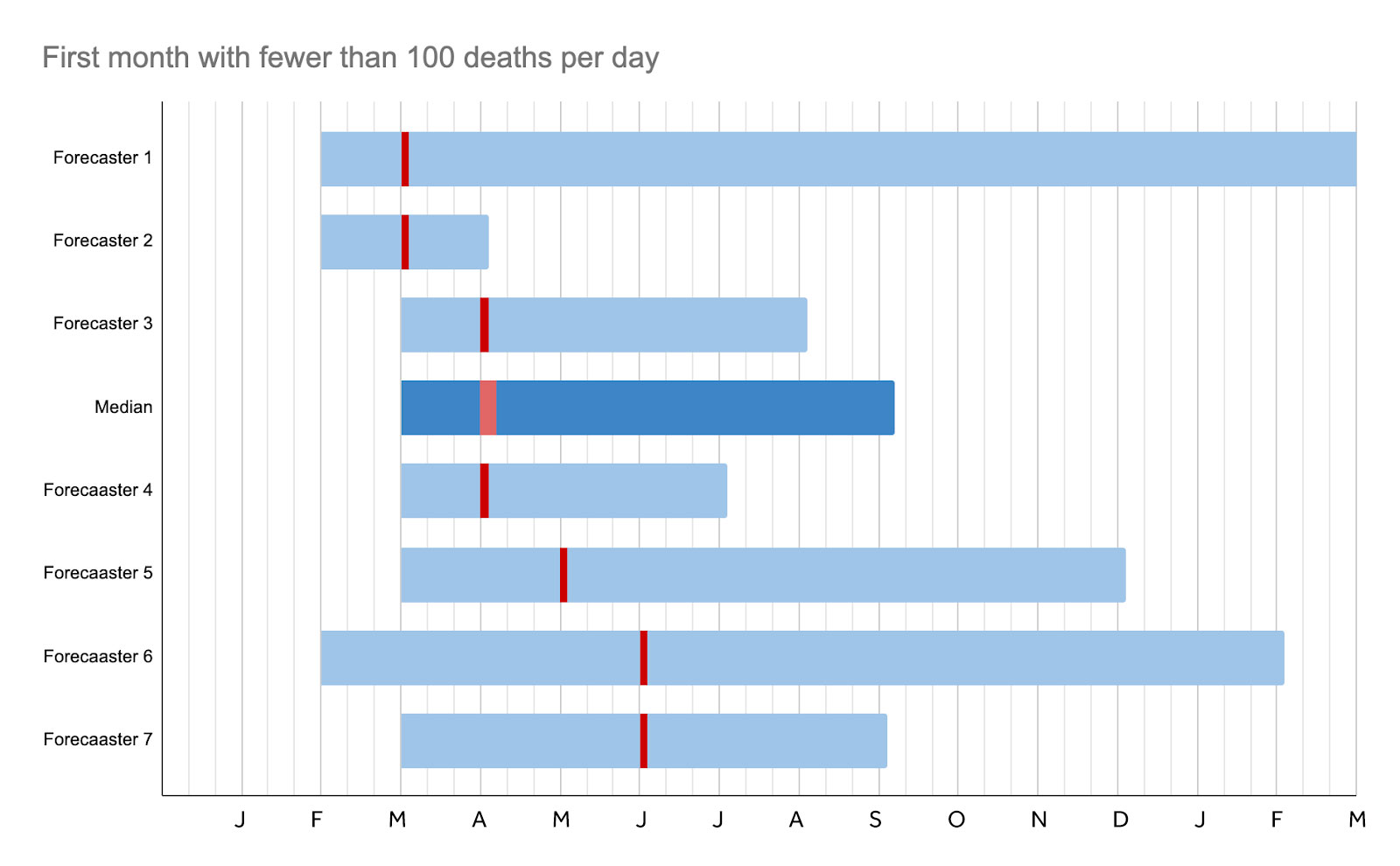

These forecasts are presented as the median estimate of the group; the principle of the “wisdom of crowds”, the idea first suggested by Francis Galton that the median of any large number of guesses will usually be fairly accurate, applies to experienced forecasters as much as anyone.

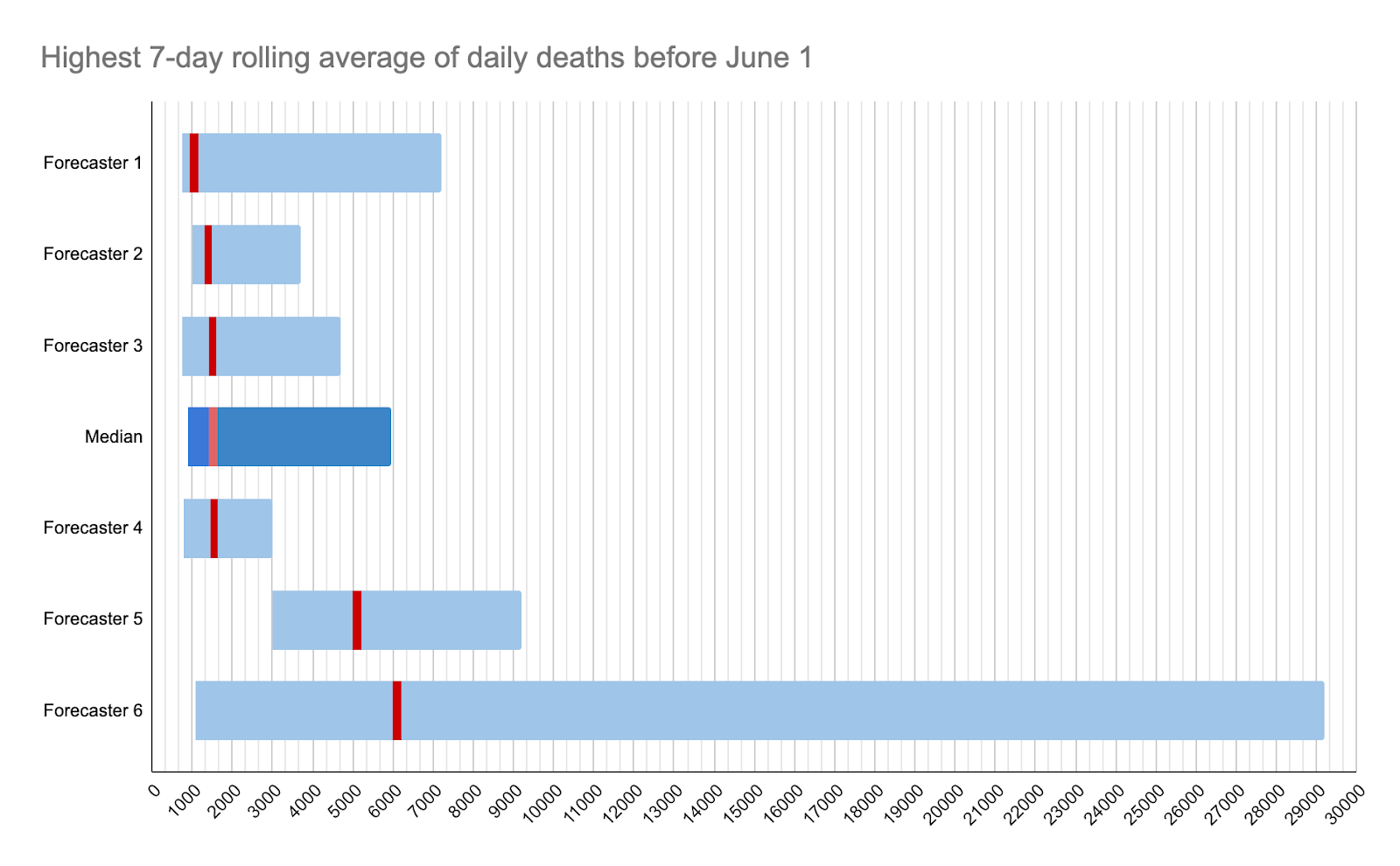

We also include our “80% confidence” interval as an expression of the uncertainty surrounding our forecast. For example, our central estimate that the death toll will peak at 1,278 with an 80% confidence interval of 892 to 5,750, means we think there’s only a 10% chance it’ll be less than 892 and only a 10% chance it’ll be greater than 5750. (The confidence intervals are represented by the blue rectangles, and the central estimates with the red lines.)

The worst of the pandemic

The median estimate of the group was for the 7-day average of daily deaths to peak at 1,278, but with an 80% confidence interval of 892 — 5,750

Alongside the predictions, we note down anonymous comments from the forecasters in the team to explain their reasoning. Among the notes accompanying this question, perhaps the most optimistic was that there is a “small chance we are at the peak now”.

On the other hand, the worst-case scenario is if the hospital system collapses and we are forced to “en mass palliate anyone over 60/65” and the most pessimistic predicted 5,000 deaths a day. The big factors were new virus strains and “poorly managed vaccination centres causing infections among the most vulnerable and highest priority population”.

However, with 160,000 infections a day currently in the UK and a fatality rate just below 1%, 1,400 deaths a day seems likely.

Another forecaster also predicted that a third wave was “likely” once the current lockdown ended, “with quite possibly the highest caseload yet, but [was] unlikely to have as many fatalities due to prioritised vaccination of elderly and otherwise-vulnerable” individuals.

A lot of this depends on whether the vaccine protects against any new strains, and how quickly those vaccines are rolled out.

The February Vaccine Target

Millions of people are currently waiting for a letter informing them of their vaccination appointment, a jab that will end a year of house arrest and often extreme anxiety. The Prime Minister has promised two million jabs a week, and tens of thousands of lives, and millions of livelihoods, depend on getting the jabs out as soon as possible.

We asked the team to forecast how many vaccine doses will have been administered in the UK by the end of February and the central estimate was 12 million, with an 80% confidence interval of 6 million to 20 million.

Among the big questions are the supply and how much political pressure there will be for the distribution network to move faster. Two more vaccines, by Novavax and Johnson & Johnson, are also expected to get approval next month and that will also increase supply.

One forecaster predicted that “Boris’s current target was 13 million for end of February: best guess is they undershoot that slightly and ramp-up only really gets going in March/April…. this has been the consistent pattern of undershooting a bit throughout the pandemic.”

So with a median estimate of 12 million, you can find out when you and your loved ones are likely to receive theirs here.

In which month will deaths fall below 100 a day?

By estimating when deaths fall below 100 a day we can get some idea of when the virus is close to beaten.

Our group estimated April as the most likely month for daily deaths to fall below this level, with an 80% confidence interval of March to August.

Among the key unknowns are new strains, and also whether hospitals get overwhelmed “which results in cascading preventable deaths”. We can estimate when deaths will fall based on first wave patterns, when it took “two and a half months to get from 1k per day to below 100 in the March-July lockdown”, although the vaccination programme might accelerate that. Generally speaking, it takes about three weeks to half the deaths, and so following an expected peak in January, death rates will half four times by late April.

At this point, one forecaster suggests, the government will open up the economy and deaths will continue around 100 a day because this will be regarded as tolerable. Another believes this figure may continue until September, by which time a combination of vaccination and infection will have introduced herd immunity.

The most “optimistic” forecast suggested that we may have got deaths down by March but that might be because “we screw up” and “have killed everyone who could possibly die from it and therefore the virus has nowhere else to go”.

The most pessimistic suggested: “If there is a less successful vaccination programme, multiple policy errors such as keeping schools open once teachers have been vaccinated but not paying attention to cases/repeated attempted opening up, or mutations of the virus, then it might be December before deaths get below this level.”

But another thought that new drugs — the most recent breakthroughs came late last week — will have reduced the fatality rate fairly soon.

January and February 2021 are going to be very traumatic months for tens of thousands of people in the UK. But to be forewarned is to be forearmed, and if you’re worried about the next few weeks you might want to gain a better estimate of how bad it will get, when your vaccine will come, and most importantly when the nightmare will be over.

And perhaps next time that Britain faces a crisis of this magnitude, we’ll have systems in place that incentivise people to tell the truth, identifying those with strong track records of forecasting, rather than turning to those who tell us what we want to hear.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe