Sabrina Carpenter’s music is pure 70s A.M. radio, country, and the occasional Prince-lite disco track. Credits: Island Records.

In 1883, Oscar Wilde addressed a group of students from the Royal Academy in their club in Golden Square. At the height of his pronouncements on the eternal relevance of great art, he delivered one of his most famous hyperboles: “Popularity is the crown of laurel which the world puts on bad art. Whatever is popular is wrong.” This sentiment remained an essential truism for the avant garde for at least a century afterwards. Surrealists and abstract artists worked to shock bourgeois audiences; the mid-century creation of “cool” inherently opposed itself to post-war conformity; musical subcultures from hippies to punks to early hip-hop and ballroom prided themselves on their insularity.

The cliché of the artist as outsider remained an essential part of the pop mythologies of several generations. Even some of the most wildly successful musicians of the late 20th century — The Beatles, Marvin Gaye, Nirvana, even Madonna — became broadly admired not just for courting enormous audiences, but for their consistent unwillingness to compromise. The masses might still gobble up whatever was served to them but they were kept partially in check by discerning and knowledgeable obsessives and critics, insistent on at least some kind of standard for artistic integrity. Even the most kitsch-hungry audiences still maintained a sense that great artists were by nature opposed to the mandates of the cynical corporate bottom line of the music industry itself. As the last young people of the 20th century, Generation X summed up the ethos perfectly: there was nothing less cool or less authentic than “selling out”.

Now, one quarter of the way through the 21st century, it seems clear that almost every vestige of the sentiment has been summarily obliterated. The reigning value system of the arts in this century — sped along by the internet’s uncanny ability to fuse micro-celebrity with social media styles of personal brand management — has been one of increasingly unabashed obsession with wild financial success, naked greed, grifting, and cynical re-branding. Beginning in the 2000s, and ramping up to a fever pitch with megastars like Lady Gaga, Drake, Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Ed Sheeran, pop music became a field of nakedly-corporate brand ambassadors and stars happily turning themselves into avatars of narcissistic self-actualisation.

Gaga and Swift, for instance, have developed armies of loyal fans by crafting broad messages of inclusivity and churning out vicarious anthems of personal achievement. Beyoncé has turned herself into an empty symbol of political and cultural revolution. Singers with little interest in art, from Ariana Grande to Doja Cat, have carved out huge successes by presenting themselves as simultaneously ultra-perfect and ultra-relatable. The message everywhere is the same: the greatest artists of our time are the most famous; they have everything, and they deserve everything. To say otherwise is not only snobbish but discredits the mass popularity into which millions of distracted, depressed, and over-stimulated people have invested all their attention and aspiration.

The usual name for this strangling monopoly of the mega-famous is “poptimism” — a phenomenon that crossed over to massive TV shows, film franchises, and fashion lines. At first an obscure internet discourse conducted mostly by critics and journalists, the term has come to signify the reigning ideology of our day, in which the old values of the avant garde are dismissed as out-of-touch and elitist (and, of course, trashed as too white, straight, and/or masculine). In the meantime, pop is associated with an enlightened sense of inclusivity, conveniently ignoring the many forward-thinking avant-garde cultures historically associated with LGBTQ artists and racial minorities in Western countries.

One accepted starting point for this contemporary discourse is music journalist Kelefa Sanneh’s 2004 New Yorker article, “The Rap Against Rockism”. In the article, Sanneh defended the aspiring popstar Ashlee Simpson after a disastrous SNL performance. Simpson’s backing track had faltered, and people quickly realised she had been lip-syncing; the blowback essentially cost Simpson her music career. But what Sanneh articulated — which he opposed to the stereotypically old-white-guy rhetoric of an early-2000s “rockism” — was a defence of Pop as product, and popstars as patently commercial projects. His defence became central to the rhetoric of many internet critics after him. What began as a fairly anodyne plea for a more open-minded idea of “authenticity” in a music industry dominated by capitalistic necessities, became a steamrolling social ethos in which artists were valorised for their business savvy and their ability to represent popular dreams of self-actualisation and economic domination. Naysayers were merely snobs and bigots, to whom the response was always the same: “Shut up and let people enjoy things.”

But it is 2025 now — and the high days of poptimism are over. Just a few months ago, Sanneh himself penned a remarkably unselfconscious article called “How Music Criticism Lost Its Edge”, bemoaning how toothless music writers have become in a world that rewards valorising the most popular, while disincentivising critics from championing lesser-known artists, knowing a review of the newest popstar’s record will generate more web traffic and revenue. Sanneh himself sounds wearied by the paradigm he helped usher in two decades ago. “Poptimism intimated that critics should not just take pop music seriously but celebrate it.” he writes. “This aligned with the changing imperatives of the media industry: on blogs, you could draw a crowd with a contrary opinion, but on social media you became a ringleader by saying things that your followers could publicly agree with.”

The first sign of this slackening grip may in fact have come from Charli XCX’s Brat. Like her contemporary Lana Del Rey, Charli XCX was a confusing figure in the 2010s. Both were initially “indie”-coded artists who went through heavily-corporatised windows of popularity, before settling down to work with specially chosen producers, honing distinct internet-savvy aesthetics. They positioned themselves on the edge of genuine stardom, and yet maintained a delicate sense that they were still first and foremost creatives, willing to make occasional sacrifices to preserve their own right to self-direction. It wasn’t unusual to find listeners and critics with a lingering distaste for poptimism, who were quite willing to make an exception for them: Charli and Lana represented an interesting compromise between poptimism’s valorisation of striving stars and older ideals of artistic integrity and autonomy.

On the surface, Brat was ostensibly a victory for the poptimist ideal of self-marketing — though if anything, there was something old-fashioned about the record. Even that spectacularly successful campaign and rollout saw Charli going against suggestions from all sides, releasing the album after a rough renegotiation with her label, with little concern for whether the record would be considered commercial enough. What resulted was an exciting cultural moment that was at least as exciting because of the music itself. Like Madonna bringing voguing to the masses, Brat came close to mainstreaming subgenres of hyperpop and 2010s electronic club music, the closest things to actual underground subcultures in that decade. Still, Brat wasn’t quite the monocultural success many wanted it to be: it made next to no dent on the US Billboard Singles Chart, it was denied album of the year at the Grammys, and a year later the streaming numbers are still nowhere near that of much bigger stars. But this only helps to preserve a sense of cool. Brat Summer became cringe quickly but it hardly took Charli XCX to the same heights as Taylor Swift. This is ultimately a good thing.

The question all of this begs is just what will fill the vacuum: what will the popstar of the near-future look like? The younger generation of up-and-coming popstars all seem cannily aware of their era. Singers like Billie Eilish, Olivia Rodrigo, Chappell Roan, Sabrina Carpenter, and even Addison Rae are all savvy young women, versed in the contours of internet discourse, plugged into specifically Zoomer kinds of nostalgia, well-trafficked in internet “aesthetic” curation, and eager to declare themselves the vigilant students of previous popstars and eras. They’ve learned the lessons of Lana and Charli, working with specific producers (often Jack Antonoff, or The 1975’s Dan Nigro), rather than massive teams of rotating writers and engineers. And they each stand in unique relation to poptimist notions of “authenticity”.

Two of these women have already reached levels of popularity to rival their forebears. Eilish initially seemed the most likely to become musically and aesthetically interesting, though she’s since backed away into far more conventional pop territory. Rodrigo has worked almost exclusively with Dan Nigro on both of her albums. And though she started off as something of a Taylor Swift copycat, her most recent record GUTS felt different. Compared to the ultra-compressed sound of contemporary pop, GUTS did spectacularly well without sacrificing great production and an actual dynamic range: certain tracks could’ve passed master on a Nineties alt-rock station. Sure, it’s pure throwback music, and the ballads are maudlin; there’s really nothing even vaguely experimental or new to be found anywhere on any of these young artists’ albums. But the anthems sounded bigger and better than just about anything else on Top 40 radio in the US or the UK Rodrigo became the first Zoomer starlet to make something that felt like good, solid, old-school pop-rock from a different time.

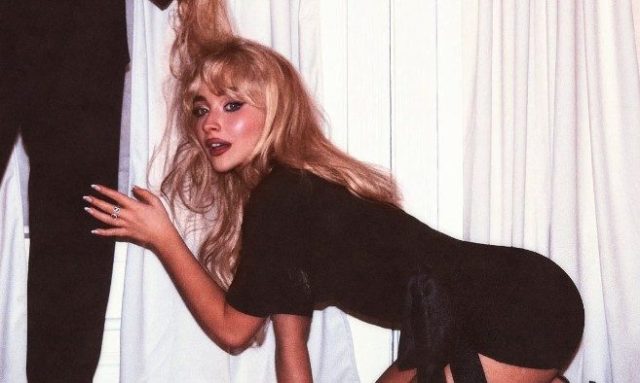

This same kind of Zoomer nostalgia for the late 20th century also marks Sabrina Carpenter and Chappell Roan’s music as well. For all Roan’s dramatic drag costumes and theatrical performances, the music is pure Eighties synth-pop and feels more cohesive and sounds better than any regular radio fare. Carpenter’s newest album Man’s Best Friend — which caused a firestorm of backlash online for its possibly-sexist album cover — is filled with lyrics straight out of the current internet discourse on dating woes and heterosexual resentment; but the music itself is pure Seventies AM radio, country, and the occasional Prince-lite Eighties disco track thrown in. Even if it’s relatively insubstantial, it still feels more “real” than most of the anonymous processed songs we’ve been subjected to for the past two decades.

Strangest of all is Addison Rae — the massively successful TikTok dance star — who earlier this year released her debut album Addison to astonishingly good reviews, becoming the ultimate poptimist redemption story. She released a slew of grainy MTV-referencing music videos, rebranded herself as a fervent student of Madonna, and hunkered down with producers Elvira Anderfjärd and Luka Kloser to produce a record full of Nineties house, trip-hop throwbacks, and obvious nods to Brat. Infuriatingly, it sounds fantastic. Rae’s savvy turn was clearly meant to dazzle doubtful audiences with its sense of curated cool, and it worked: comments online are full of listeners in awe of the change, saying things like “this is how you rebrand”. It doesn’t matter whether she’s a particularly strong singer, or whether she actually wrote a single line. What matters to people is the sense that she played the re-brand game the smart way. Rather than chase the anonymous sounds of the charts, Rae pursued something that felt cohesive, and gestured toward an older sense of cool. It shows that the future for aspiring popstars like her may lie in cultivating good taste.

This is the strange legacy of the last days of poptimism. What began as a rejection of previous standards of cool has left us with decades of empty pop music, uncritical critics, and huge fandoms deeply resentful of anyone who suggests that the pop idols they worship are not brilliant simply because they’re massively wealthy and successful. The decline of poptimism has opened space for aspiring popstars to define themselves by their taste again. This is a step in the right direction. Still, the return of really exciting and adventurous pop music requires the return of authentic subcultures, too. This is going to be difficult: the victory of poptimism hampered the ability of subcultures to protect their sense of cool, just as it strangled the ability of critics to argue for anyone other than the most popular musical artists.

“The only alternative to criticism,” the great film critic Pauline Kael once said, “is advertising.” We have lived for many years now in a world that has increasingly collapsed the boundaries between the two. The job of critics now has to be to reject the market; to advocate again for neglected artists, and a sense of cool, and to push back against stan culture. But this also means recognising and celebrating better pop music when it appears. If the young popstars are any indication, and the years of poptimism are giving way to a slight chance at a change for the better, then what artists need most is to be empowered to shift towards making good music for its own sake. This can only be done through the establishment of trustworthy critical voices. Such trustworthiness can only appear when enough people insist that art is not better simply because it’s more popular, and that commerce will always be a partial enemy to art. Do so long enough, and history tells us that audiences will eventually adjust. And it is at this point, when audiences really begin to adjust, that popular artists become free to make something truly new.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe