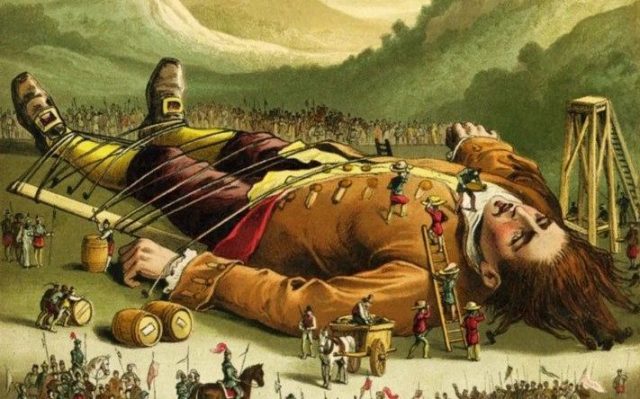

In Gulliver’s Travels, the Tory Swift maliciously unsettles the progressive thinkers of his time. Credit: Creative Commons License

Donald Trump wants to shrink the American state and Pete Hegseth, his Secretary of War, wants to shrink the top brass. He has ordered his military officers to lose some weight, arguing that there are too many gross generals, corpulent colonels and massive majors around the place. The same is true of American police officers, who seem to be recruited for their beefiness. The fact that they can’t run is the reason why so many suspects get shot in the back. British police officers are expected to be fit, and male officers to be of a certain height. An uncle of mine, not the most savoury of characters, applied to join the police force and was turned down for being an inch or so too short. This saved the general public a number of stitch-ups, fabricated evidence and planted bags of dope. The problem with reforming the police is the kind of people the nature of the job attracts. Another uncle was even smaller than this one, and served in submarines during the Second World War. As a child I believed that all submarines, given their cramped space, were staffed by midgets.

American men are generally taller than British ones, and tend to move in a different way. A student on a US campus once told me he knew I was English by the way I walked. Hegseth stands with his arms hanging loose but slightly bent like a gorilla. In the 19th century, Irishmen were taller than their British counterparts. We know this from the statistics kept by the British navy at the time, which had a fair number of Irish recruits. Many of them would have been brought up eating almost nothing but potatoes, and potatoes contain almost everything you need for a healthy diet. This was also a reason why the Irish made such good navvies, building Britain’s roads, canals and railways. Upper-class men are for the most part taller than working-class ones. In the gentlemen’s toilet at the Cambridge Union there’s a sign on a very high beam which reads “Mind Your Head”, but given the size of some of the young Rt. Hons who frequent the place it may not be intended as a joke. When I was a student at the place myself I felt like a stunted Northern prole scurrying among braying Brobdingnagians, of whom more in a moment.

As you grow older you may not grow smarter but you certainly get smaller. Just look at pictures of Prince Harry next to his grandmother. Jesus Christ is believed by some of his less theologically sophisticated followers to have been exactly six foot tall. One wouldn’t want a short guy as a saviour. Given the age in which he lived, however, he was probably about the size of Ronnie Corbett. As for Shakespeare, you could probably have put him in your pocket. On the other hand, Napoleon, generally considered to be gnome-like, was actually the average height for males of his time. Seeing him as dwarfish was just British propaganda. I used to be exactly the same height as Mick Jagger, but this is no longer true unless we’re shrinking at the same rate.

There is a Lilliput Press in Dublin, run by a suitably diminutive publisher. It’s named of course after the pint-sized characters in the Dubliner Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels. During his stay in Lilliput, Swift’s protagonist is much too gullible, which is the reason for his name. He takes on the conventions and perspectives of his hosts far too zealously, hotly denying the charge that he has had sex with a Lilliputan woman without once raising in his defence the physical impossibility of doing so. By contrast, when he arrives in Brobdingnag, a land populated by giants, he refuses to adjust to their form of life and remains obtusely Anglocentric. He delivers a self-satisfied account of British customs and institutions to the king of the country, from which the king “cannot but conclude the bulk of your natives to be the most pernicious race of little odious vermin that Nature ever suffered to crawl on the surface of the earth”. This isn’t quite the impression Gulliver intended to give.

The question is what distance you need to establish between yourself and what you confront in order to give a true assessment of it. Gulliver’s problem is that he’s either too close to a culture to criticise it, or too remote to do so adequately. As Bertolt Brecht remarked, only someone inside a situation can judge it, and they’re the last person who can judge. Swift was Anglo-Irish, and thus knew a good deal about living on the cusp between two civilisations. If he hated a lot about the British establishment, he also detested a good deal about the people of Ireland. His satire isn’t polished and urbane, but savage and polemical, shot through with fury and disgust.

At one point in the novel, Gulliver wonders whether there’s a race of creatures somewhere in the world to whom the outsized Brobdingnagians appear as minuscule Lilliputans. Might there be an infinity of sizes? What is the “proper” height to be? The answer, of course, is that there is no such thing. Human beings like Gulliver think that they’re the right size; but this, as Ludwig Wittgenstein points out, is like a man exclaiming “But I know how tall I am!” and placing his hand on top of his head. This philosophical fall guy hasn’t grasped the fact that size is relative to a norm, which isn’t something purely subjective. Otherwise we would have to say that everything is just the size, weight and shape that it is, which is to say nothing at all. We are the right size for our world, sure enough, but that’s because we’ve shaped it to suit us.

The problem is that there are many different norms, as Gulliver’s Travels demonstrates. One of the book’s purposes is to show how at least some of one’s own norms and conventions may be universal, but not necessarily in ways we should find gratifying. The Lilliputans differ from humans in various ways, but there are also ways in which they are disconcertingly similar. They, too, are excessively ambitious, mean-minded, foolishly proud of honours, ridden by political rivalries and so on. In one sense, this lets humanity off the hook: if our own vices are to be found everywhere, this makes us less responsible for them. But it also brutally undercuts those utopian thinkers who hope to stumble upon an ideal society somewhere over the ocean. By ascribing all-too-human qualities to beings so physically alien to us, the Tory Swift maliciously unsettles the progressive thinkers of his time.

Like Gulliver before the king of Brobdingnag, colonialism comes face to face with civilisations very different from its own; but by remaking them in its own image it refuses to be disturbed by their difference. Gulliver has the chance to objectify his own way of life, seeing it for a moment through the estranging eyes of the horrified king; but he refuses to allow his identity as a chuckle-headed Englishman to be thrown into question, and the Irishman in his author invites us to smile at this obduracy. The joke, however, is finally on us. In the final part of the novel, Gulliver finds himself among the Houyhnhnms, a race of wise and virtuous horses; but instead of trying to see them judiciously, as he does the Lilliputans, he ends up yearning to be one of them himself. He begins to think of himself as a horse, chatting to his own horses for several hours a day and finding the human smell of his wife and children intolerable. He swings from a puffed-up pride in his own kind to a pathological hatred of them. He’s always either too deeply in or too far out, too close to judge or too distant to do so, too rigidly normative or too ready to throw norms to the winds.

Swift’s hero, in a word, finally goes mad. He has objectified his own culture to the point where he loses touch with it altogether. Either you refuse to have your identity called into question by a different way of life, or you idealise that way of life in an absurdly uncritical fashion. The sentimental liberal who refuses to breathe a word of criticism of female genital mutilation in Africa is simply the flipside of the bigot for whom cultures other than his own are naturally inferior. The liberal’s problem is one of cultural relativism: all societies do things in their own peculiar way, and that’s just fine. It’s a deeply condescending viewpoint: sex trafficking is okay for them but not for us. To claim that something is acceptable because it’s part of your culture is to claim that it’s alright to do it because it’s what you do. There have been more persuasive arguments.

All human cultures are contingent. They arose and evolved in largely random ways, and none of them is based on any divine or metaphysical necessity. If God exists he has a special regard for absolutely none of them, not even the United States or Israel. Jesus was too busy reviling the Pharisees to walk on our own green pastures. There might just as well not have been an English or Malaysian people, and there might not be at some point in the future. History is littered with the husks of civilisations that believed they would last forever. Some British values in the past would be deeply objectionable to Britain in the present, and most of what’s claimed to be peculiarly British — honour, fair play, modesty, decency, a racist police force, and so on — can be found in a host of other societies as well.

None of this implies that one shouldn’t value aspects of one’s own culture. It’s just that one should do so ironically. To live ironically is to commit oneself to a course of action or form of life while recognising its fundamental contingency. The same is true of the individual life: you play tennis and stack the dishwasher while acknowledging that none of this will ultimately matter because in the end you will be dead. That’s no reason to stop doing such things, but it may prevent them from filling your attention to the point where you can’t see around and beyond them. Jonathan Swift was a supreme ironist; Gulliver’s problem is that he doesn’t know the meaning of the word.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe