Valerie Stivers

4 Oct 2025 - 12:06am 11 mins

In the dark, pre-election days of October 2020, a big investigative feature by the veteran journalist Ruth Shalit Barrett appeared in the November issue of The Atlantic magazine. “The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports Among Ivy League-Obsessed Parents” concerned wealthy families’ attempts to game elite college admissions by developing their offspring’s talents for low-popularity sports like fencing and squash. The story displayed the kind of in-depth original reporting and cultural relevancy that the magazine is known for. And it made a splash. Yet within two weeks, The Atlantic had issued a retraction, accompanied by a denunciation of the author and her work that was noteworthy, even in the peak-denunciation era, for its length, viciousness, and the opaque nature of her alleged crime.

In 2022, Barrett (Shalit is her maiden name) sued The Atlantic for defamation and breach of contract. This summer, the parties settled the suit, to the tune of more than $1 million. (Some of the counts were dismissed.) Nonetheless, “The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports” remains retracted on The Atlantic’s website, available only in the oddly purgatorial form of a PDF, and an edited version of the original editor’s note that accompanied the retraction remains, and still represents the magazine’s core claims against the writer.

For a freelancer to sue a billionaire-owned prestige outlet and receive a decisive settlement is an unusual occurrence, and seems to suggest missteps on the part of The Atlantic. The publication prides itself on having the highest journalistic standards. Its current website displays a marketing banner touting “Accountability. Transparency. Independence.” If The Atlantic’s claims against Barrett were so transparent and accountable, why did it settle? And if they weren’t, why did the publication make them in the first place?

In the dark, pre-election days of October 2020, a big investigative feature by the veteran journalist Ruth Shalit Barrett appeared in the November issue of The Atlantic magazine. “The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports Among Ivy League-Obsessed Parents” concerned wealthy families’ attempts to game elite college admissions by developing their offspring’s talents for low-popularity sports like fencing and squash. The story displayed the kind of in-depth original reporting and cultural relevancy that the magazine is known for. And it made a splash. Yet within two weeks, The Atlantic had issued a retraction, accompanied by a denunciation of the author and her work that was noteworthy, even in the peak-denunciation era, for its length, viciousness, and the opaque nature of her alleged crime.

In 2022, Barrett (Shalit is her maiden name) sued The Atlantic for defamation and breach of contract. This summer, the parties settled the suit, to the tune of more than $1 million. (Some of the counts were dismissed.) Nonetheless, “The Mad, Mad World of Niche Sports” remains retracted on The Atlantic’s website, available only in the oddly purgatorial form of a PDF, and an edited version of the original editor’s note that accompanied the retraction remains, and still represents the magazine’s core claims against the writer.

For a freelancer to sue a billionaire-owned prestige outlet and receive a decisive settlement is an unusual occurrence, and seems to suggest missteps on the part of The Atlantic. The publication prides itself on having the highest journalistic standards. Its current website displays a marketing banner touting “Accountability. Transparency. Independence.” If The Atlantic’s claims against Barrett were so transparent and accountable, why did it settle? And if they weren’t, why did the publication make them in the first place?

At no point has The Atlantic disavowed the basic premise of Barrett’s story: high-level participation in niche sports, once a promising strategy to land a spot at an elite college, has become an arms-race among wealthy families, with diminishing results. Instead, the conflict has centered on a welter of supposed factual errors suggested by Erik Wemple, then The Washington Post’s media critic, in a series of columns about the piece. The publication has also questioned the accuracy of Barrett’s representation of “Sloane,” a Connecticut sports mom who participated in the story on the condition that she and her college-hopeful children would not be identifiable. Concerned that the publication was not honoring its commitments, Sloane misled The Atlantic’s fact-checkers in the 11th hour, and entirely withdrew her cooperation with the magazine post-publication.

On one side is the narrative presented by The Atlantic in current and past versions of the editor’s note that accompanied the story’s retraction, and in an internal memo to staff from editor Don Peck. In this telling, The Atlantic fell victim to a serial plagiarist and journalistic untouchable, and only realized this thanks to Wemple, who is now a media reporter for The New York Times.

On the other side is Barrett, who contends that “my niche-sports article was published in October of 2020, at the zenith of America’s great racial reckoning and at the height of social justice-infused callout campaigns,” as she told me. During this time period, elite liberal publications such as The Atlantic were highly sensitive to protecting themselves from allegations of racial wrong-think. This, according to Barrett, “created a perfect opening for The Washington Post — a publication that is unique among major journalistic outlets in allowing its pages to be used to settle scores and malign those who have hurt the newspaper — to attack me.” Wemple, reached via telephone, called this idea “preposterous.”

Nonetheless, at the time he penned a series of critical stories on a single magazine article, questioning the facts in Barrett’s story, doing re-reporting of his own, and assailing her credibility, repeating claims that she had in the past “embellished quotes and exaggerated details,” “stretched quotes and embroidered details,” and “mishandled quotes and story points.” Barrett denies all such allegations, calling them “pure innuendo and insinuation” and “made-up nonsense.”

Barrett is known to many as a notorious media figure of the Nineties, when her meteoric career fresh out of college as writer for The New Republic and other prestige venues was marred by a plagiarism scandal. She was shown to have lifted minor, boilerplate-type sentences from other writers’ work in four brief instances. She was also an enfant terrible of sorts in the Washington of the period, and a frequent target of media-gossip columnists. Her work did draw many allegations of factual inaccuracies. These often, however, seem to be of a vague or misleading type when you really look into them. Defenders — among them, Leon Wieseltier, The New Republic’s literary editor in those years — have represented much of the controversy as a natural result of a journalist doing hard-hitting reporting.

Detractors, not least David Carr, the legendary media critic, have called Barrett “tremendously self-involved,” “not particularly self aware,” and “a one-woman journalistic disaster area.” (To be fair, she was notoriously disorganized, overcommitted, and late with her deadlines.) Carr has been posthumously canonized, but during his time as the editor of the Washington City Paper in the Nineties (where Wemple also worked), he kept up a steady stream of extremely nasty Barrett-bashing via a regular feature he called “That Darn Ruth.” Some of Carr’s commentary, such as calling Barrett “a kinder-genius, complete with frilly socks” and remarking on the color of her lipstick, seem to bear out her remarks to me that part of her negative reception was due to misogyny.

On the telephone, Barrett is an overwhelmingly voluble conversationalist, and seems to have been driven at least a little crazy, a la Bleak House or Kafka, by defending the details of her case. She provided me with hundreds of pages of documents, including her complaint, a memorandum opinion and order from the federal trial court, an “omnibus write-up” on the case, a summary of the omnibus writeup in case I didn’t want to read its 51 pages, PDFs of relevant articles, screenshots of text messages with editors, and more. These documents presented a compelling counter-narrative to the one put forth by The Atlantic.

The Atlantic editor’s note currently attached to Barrett’s retracted story on the magazine’s website begins: “After The Atlantic published this article, new information emerged that raised serious concerns about its accuracy, and about the credibility of the author, Ruth Shalit Barrett. We have decided to retract this article. We cannot attest to the trustworthiness and credibility of the author, and therefore we cannot attest to the veracity of the piece in its entirety.”

The note goes on to explain that Barrett was complicit in a deception perpetrated by Sloane, regarding the number of children she had, which Sloane included as a masking detail. And it reports “several” additional errors: a thigh injury should have been described as a “skin rupture” rather than “a deep gash”; a lacrosse family was erroneously said to live in Greenwich, Conn., when in truth they lived in another town in Fairfield County; and some private backyard hockey rinks characterized as “Olympic-size” were “large, but not Olympic-size.”

The note also mentions incidents in “1994 and 1995 in which plagiarism and inaccuracies were found in Ms. Barrett’s reporting,” and explains that “we decided to assign Barrett this freelance story in part because more than two decades had separated her from her journalistic malpractice at The New Republic and because in recent years her work has appeared in reputable magazines. We were wrong to make this assignment, however. It reflects poor judgment on our part, and we regret our decision.”

In previous versions of the note, The Atlantic claimed that Barrett “left The New Republic” in 1999 “after plagiarism and inaccurate reporting were discovered in her work.” Both the previous and current versions of the note mention that the story ran under the byline Ruth S. Barrett, asserting that the magazine “should have included” the name that she used in her byline in the Nineties, strongly implying that the Ruth S. Barrett byline was an attempt by Barrett to conceal her identity.

Barrett, in her complaint against the magazine, contended that she overlooked the deception of the magazine’s fact-checkers by the source, Sloane, in order to honor her agreement to keep her source confidential, and that her behavior was justified, given the magazine’s failure to honor its commitment to sufficiently mask the source’s identity. The court did not deny the truth of this claim, but dismissed the count regarding it.

However, the court accepted the statements of fact behind several other counts: the magazine originally misrepresented the circumstances of Barrett’s departure from The New Republic in 1999; and the author has never sought to conceal her identity via her byline. Barrett explained in her complaint that she’d written under the name Ruth Shalit Barrett or Ruth S. Barrett since her marriage in 2004. She also provided me with the receipts to prove that she added the “S.” to The Atlantic’s proposed byline of “Ruth Barrett” to render herself more identifiable.

The court agreed with the plaintiff that The Atlantic’s statements could have been “capable of defamatory meaning,” and that “a reasonable reader could infer two negative narratives, both of which ‘imply unstated defamatory facts’: first, that Ms. Barrett sought to conceal her identity and distance herself from her work in the 1990s; second, that her history was sufficiently unsavory to warrant her doing this,” according to an opinion of the trial court allowing some of her claims to go forward before a settlement put an end to the matter.

The Atlantic settled just before Barrett’s lawsuit reached the discovery phase — that is, just before its editors would have had to start turning over their emails. In public statements it has presented the incident as a result of the magazine’s high-mindedness and high standards.

To momentarily pierce the veil of bullshit: the factual inaccuracies revealed in the magazine’s correction are extremely minor, could easily have been corrected in an online version of the piece, and do not seem to justify a major retraction. Such things are pretty common, even in exhaustively fact-checked stories at premium outlets like The Atlantic, and are not usually the occasion of high-profile defenestrations.

The deception of the fact-checkers is a blacklisting-level offense, possibly, depending on the writer’s clout and the publication, but again, it and the other minor alleged errors don’t quite seem to warrant the total demolition of Barrett’s reputation carried out by the editor’s note and retraction. Nor does it account for the publication’s other acts of apparent bad faith. For just one example — there are many — The Atlantic editor’s note even today mentions allegations by Sloane’s attorney that Barrett made additional mistakes in her story.

In a letter presented to The Atlantic’s attorneys by Barrett’s attorneys, portions of which were made available to me, Barrett claims to have conclusively demonstrated to the publication that these allegations were unfounded. She provided The Atlantic with documentation on two details questioned by Sloane’s attorney: the existence of a beach house and a makeshift basement fencing strip; and she had receipts that editor Don Peck had received the evidence. So why is a transparent and accountable publication still mentioning these allegations in its editor’s note, except to make Barrett look bad?

The editor’s note’s declaration that “we cannot attest to the trustworthiness and credibility of the author, and therefore we cannot attest to the veracity of the piece in its entirety” suggests an answer. A magazine article is, by definition, a quantifiable event, whose veracity is not a mystical quality, but in fact can be determined through the well-established practices of sourcing and fact-checking. The Atlantic fact-checked Barrett’s story before publication, and then again, by its own account, did so forensically, afterward. Despite Wemple’s exhaustive spit-balling and The Atlantic’s very best efforts, the only “errors” it has exposed are of a flimsy and irrelevant nature: a “skin eruption” rather than a “gash,” whatever that means, the square-footage of a hockey rink, and so on.

The writer’s “trustworthiness and credibility,” however, is a different matter. These qualities depend not on her work, but on public perception. The magazine’s suggestion is that Barrett’s history and reputation — exceedingly well known before the article was published — disqualified her from inclusion in its pages. However, it might be more fruitful to look instead at the particular conditions of 2020.

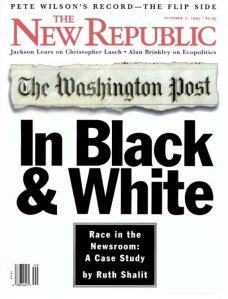

Wemple wrote multiple stories for The Washington Post about Barrett’s piece at the time of its publication. The first, entitled “Ruth Shalit Just Wrote for The Atlantic, Would Readers Know it From the Byline?,” appeared on Oct. 24, 2020, and appears to be the origin of the byline scandal. Wemple’s story also made reference to a legendary and controversial 13,000-word feature Barrett (then Shalit) wrote for The New Republic in 1995 that was critical of racial diversity initiatives in The Washington Post’s newsroom.

Barrett’s 1995 story was a tour de force, and made many well-sourced points on the divisive nature of diversity initiatives, the negative consequences of choosing applicants by race rather than by merit, and the irritating and demoralizing banalities of diversity training. The writer was 24 years old when the piece appeared, and her wunderkind-reporter status was obviously deserved. She reached the prescient conclusion that when newsrooms make the promotion of social justice a priority, they hamper the production of news and fundamentally distort its contents.

In the 1995 essay, Barrett acknowledged the Post’s troubled racial history — an all-white newsroom, protests over racist coverage — but quoted multiple staffers anonymously and one on the record with concerns that its commitment to establishing proportional representation was diluting the talent in the newsroom. Given the size of the candidate pools, she demonstrated, proportional representation with top talent was “flamboyantly unrealistic” and she confirmed this with quotations from a memo by the paper’s own recruitment expert. Moreover, these measures weren’t making anyone happy. Both white and black staff members were now complaining of discrimination.

This is not to say that the purity police came for Barrett in 2020 as retribution for a 1995 story. However, one might suspect that she was both denounced and purged for racial wrong-think — which is to say, purged because it was possible, and it was a fun thing to do at the time, and made the purgers feel more secure about their own jobs. The mere mention of a story like “Race in the Newsroom,” in Wemple’s column would not have been lost on editors at The Atlantic in 2020. Wemple responds that it is “simply not true” that racial politics in 2020 had anything to do with his reporting on Barrett. “I do my work the same regardless of what decade it is,” he said.

In a Nov. 2 follow-up story for the Post, Wemple mentioned an anonymous staffer at the magazine who “raised concerns” in a meeting about the “racial implications” of a passage of Barrett’s story on teen sports, and who “pointed to a connection between that language and the mentality suffusing the author’s long-ago investigation of the Post.” A little more digging reveals a story in The New York Times in 1995, quoting a black reporter from The Washington Post as saying, “the article was the most racist piece of so-called journalism I have read in modern times.” What magazine, in post-George Floyd 2020, would have felt safe platforming Barrett?

Bottom line: the core of Barrett’s story on niche sports was beyond reproach — and in fact her findings were validated in 2023 by a group of economists at Harvard. And her 1995 reporting was a textbook example of a lost form of hard-hitting investigative reporting. It’s The Atlantic’s failure that it published a true story only to retract it.

It’s disappointing to see The Atlantic violate its own standards and the standards of journalism to distance itself from Barrett. The original editor’s note appears to have been written not to present a fair portrait, or even the correct facts about Barrett’s history, but in order to align with the publication’s politically motivated and cancel-culture-safe inner truth. The current version of the note does the same thing in even more disjointed fashion. Anna Bross, senior vice president of communications for The Atlantic, commented via email that “the story remains retracted and that will not change.”

This kind of activist journalism is poor journalism, and is exactly what Barrett’s article in The New Republic predicted would happen as the profession moved to prioritize “diversity” as a social-justice cause. Muddled prose, exaggerated smears, and the weaponization of fact-checking are the tools of the trade, and present a desired truth, instead of the real one.

Barrett has been a victim of this since the beginning. For just one example, “Race in the Newsroom” has been widely reported to contain errors. And it did. Barrett lists four in one of her documents. But the errors are also widely mischaracterized.

In the most serious, she wrote that a city contractor named Roy Littlejohn “served time” on graft charges during the notoriously corrupt reign of DC Mayor Marion Berry. Wemple mentioned this in 2020, writing that “Littlejohn wasn’t even charged with such an offense.” Carr did the same in 1999, noting that “nothing of the sort happened.” Actually, something close to it did happen: Littlejohn was the target of an undercover probe for corruption. Barrett — a 24-year-old reporter, working on a 13,000 word piece, on deadline, made a regrettable error. But suggesting that “nothing of the sort happened,” without more, wasn’t quite right, either.

“The Post’s response to ‘Race in the Newsroom’ was the dawn of fact-checking as a pretext for discourse policing,” Barrett wrote to me in a text. “Rather than address the substantive critique I was making, WaPo sent legions of fact-checkers after me to assert that the piece was riddled with staggering errors. [Their] claim that my article was rife with errors was itself false. But this was the view that congealed and took hold.”

Barrett, an investigative reporter of great capacities, left Washington in 1999, after smear-level media association of her with an unrelated journalism scandal (that of fabulist Stephen Glass, also an employee of The New Republic) made her position untenable. In 2020, she was writing about sports moms — and even this wasn’t allowed. Her silencing has been a loss to the profession, and has been a forerunner of the wider silencing of discourse we see today in the legacy media. Only the bad reporters and craven insinuators are left, and they remain un-fact-checked.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe