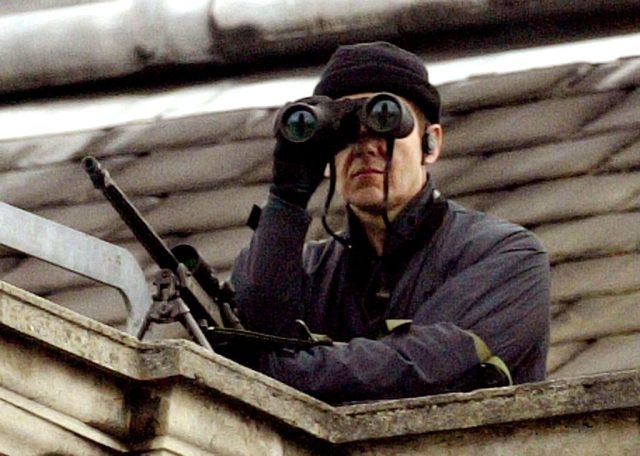

They’re watching. Ian Waldie/Getty Images.

At nearly 2.5 million signatures, the petition against the Government’s proposed digital ID scheme has vastly exceeded the threshold — 100,000 — for parliamentary consideration. The plans have been decried by political figures ranging from the hard Left (Jeremy Corbyn) to the populist Right (Robert Jenrick). All the while, Cabinet ministers claim that the new IDs are designed to impair illegal labour rather than to tighten the grip of the state on law-abiding citizens.

Few seem to believe those claims. But the more significant phenomenon is not the particular tendencies of this or that politician: it is the struggle of this government, and of all modern governments, to maintain control of information in an age when the internet has begun to pose a dangerous threat to that control. Today, information can be distributed far more easily, widely and quickly than in history’s most searing periods of revolution. It is a reality that traditional mechanisms of government find hard to accept — a discord that can have devastating consequences.

Seen through this lens, the recent flare-ups of the free speech debate — the arrest of Graham Linehan, the reprimanding of Starmer by Donald Trump over free speech in the UK, the introduction of the Online Safety Act — can all be understood as responses to the challenges to government posed by the new technology. Societies across the globe are still digesting an extraordinary change, and the crises spreading across the world are in part a reaction to it.

Yet if governments now seek to control information via new means, their desire to do so is nothing new. And, as Elias Canetti, a Nobel laureate for literature, wrote in Crowds and Power, secrecy is a fundamental component of power. Governments have always sought to monopolise information and to shape it. They have often kept large swathes of it secret, whether it is records of government meetings or the tabs they are keeping on criminal gangs and geopolitical adversaries. At the same time, they have generally sought to censor materials which are contrary to their vision.

Any politician who is truly ignorant of this basic fact of history probably shouldn’t be anywhere near government. For if, in theory, we object to secrecy: in practice, citizens of Western liberal democracies have been quite happy to accept this reality. This is why, for instance, UK government files are kept secret for 20 years before being released to the public. No politician has ever contested this rule. That is because, until now, all politicians shared the unspoken opinion that secrecy was an important part of government; until, that is, they started leaking excerpts of cabinet meetings to friendly journalists, a symptom of the transformations now underway.

Though secrecy of information has always been a key plank of political authority, there are of course different tiers of secrecy enforced by governments. As Canetti noted, autocracy of information has often been a symptom of dictatorships. The Stasi’s network of “secret informers”, members of the public who informed on each other, remain in the living memory of the former East Germany. I saw a similar phenomenon myself in The Gambia. There, in the years preceding the end, in 2017, of Yahya Jammeh’s regime, I was doing research on Gambia’s precolonial history. Such was the fear of government informers that, at any mention of Jammeh’s increasing turn to authoritarianism, people’s eyes would cloud over and they went quiet.

It is a reaction that would have been visible at many other places and points in history. Take the Papal Inquisition, set up by the medieval papacy to police heretics like the Cathars. Where Starmer’s digital ID proposes authority over our biometric information, in late medieval and early modern Europe the Inquisition sought authority over what it too deemed to be the most important information about citizens: the purity or otherwise of their religious faith.

Having almost died in the 15th century, the Inquisition was revived as a state-backed institution in absolutist Spain, and then in Portugal, from the late 1470s onwards. The Inquisition soon became a bulwark of what were then the most powerful states in Europe, useful for attacking dissenters and confiscating their property. A cornerstone of the inquisitorial judicial process was secrecy: not only did witnesses have to swear that they would keep all aspects of the trial secret, but the accused were never told who had accused them, or even what they had been accused of.

We can understand what this meant for the human experience of power only through individual cases, which — fortunately for historians — the Inquisition archived meticulously. In 1665, for instance, the Inquisition arrested Crispina Peres, who was the most powerful trader in the port town of Cacheu (today’s Guinea-Bissau, West Africa). Peres was charged with “witchcraft” after several years of interrogations led by an ambitious cleric. Her downfall came in spite of an uprising of almost 1,000 troops marshalled by the local king, who was her ally. She was eventually deported via the Cape Verde islands to Lisbon, a journey of more than 2,500 miles. Peres languished for three years in the inquisitorial jail, at one point spending over 12 months in her cell without being summoned for an interview. By the time she returned to Cacheu, after confessing her guilt in an ritualised form of penance known as an Auto da Fé, her health was shot through and the power she had held as a trader in Cacheu was gone.

For historians like me, the Inquisition’s insistence on secrecy is a gift. Because of their desire to rule out anyone whose evidence was partial, Peres and her husband Jorge spent long depositions mentioning all of their enemies, offering in the process a unique window into the daily lives of people who lived so long ago in West Africa. As her husband Jorge said, her actions were nothing out of the ordinary in Cacheu. Indeed, some of her main accusers freely admitted to partaking in the same African religious ceremonies as she did. In essence, she was arrested because her power threatened the secrecy which was the cornerstone of the political authority which Portuguese institutions of empire were developing in West Africa.

How does all this relate to the debates over digital ID and freedom of speech — and the recent comments by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and many politicians, over what the Government can and can’t do to police speech and information on the internet? The answer is that breaches of secrecy have always been seen by political leaders as constituting a major threat to power. This is an insight that helps us understand several key global events of the past 15 years.

The Wikileaks affair, which led to the multi-year solitary confinement of Julian Assange in HMP Belmarsh, is about more than the specific information that Assange leaked. Instead, the harsh punishment stands as a warning to any others who might seek to challenge the secrecy of our political elites. For them, Assange’s real threat lay not so much in the details of what was revealed as in the structural challenge posed by Wikileaks to their view of politics, which required their unquestioned right to secrecy in the exercise of government. Nor has this relationship between secrecy and power been just a Western phenomenon, as the widespread “secret societies” in Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa make clear.

In the 21st century, political elites impose censorship not only by punishing individuals, but through the actions of increasingly nebulous organisations. In June 2019 — two months after Assange was removed from the Ecuadorean embassy in London — an alliance of the world’s biggest broadcasters founded an organisation whose putative goal was to combat misinformation. The Trusted News Initiative (TNI) is an alliance of the world’s biggest publishers: hosted by the BBC, it includes major news agencies, major newspapers from the UK, the US and abroad, and big tech companies such as Google and its subsidiary YouTube.

Within a year, the TNI played a key role during the Covid pandemic in censorship of “fake news” — including, in the first 18 months of the pandemic, the mere suggestion that Covid-19 could have leaked from a lab in Wuhan. Those from Left (such as me) and Right who questioned whether strict lockdowns were necessary, and whether a cost-benefit analysis including real-world harms to young and old in the West and the Global South should not be considered, had their views ruthlessly suppressed by the TNI in the press and in social media — with a price that the whole world is now paying.

The TNI was seen by conspiracists as a key plank in the “plandemic”. But sceptics of a different sort would see the TNI as a weapon created and deployed by political elites to defend their monopoly of information. In this sense, it doesn’t really matter whether the information is true or false. What matters is the importance of secrecy to political authority, and the vicious efforts which those in power will make to maintain their grip on this secrecy.

Thus it is no surprise that new research is revealing the lengths that the West’s political leaders are taking to impose their preferred information paradigm. During Covid, Emmanuel Macron, the President of France, tried personally to communicate in private with the then CEO of Twitter, Jack Dorsey — to precisely what end, we still do not know — while French state-affiliated NGOs sought special access to Twitter’s internal data and content moderation process. Similarly, the UK, like the EU, has sought backdoor access to digital communications services such as WhatsApp. Woe betide those who do not comply: Pavel Durov, the defiant founder of the Telegram app, was arrested last year.

All this shows the depth of the political reaction now in place to shore up Western authorities’ control of information, in which digital ID is a further move. Yet the accompanying debates often show a general lack of structural understanding of the historical relationship between political power, secrecy, and information. In its pugilistic response to the Linehan affair and the Online Safety Act, the Right shows its naïvety: these instincts to control information are a fact of political life.

But the Left is guilty of comparable naïvety in its railing against conspiracy theories and the Right’s alleged predisposition to swallowing them. While egregious conspiracy theories should of course be called out, the Right — contrary to the dismissive claims by the Left — is correct to see conspiracy as part of power. The Left, at times, has shown similar attentiveness. Indeed, prior to their 1917 coup, Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks had a strongly conspiratorial critique of the levers of capital. And, in terms of more prosaic politics, Boris Johnson, Keir Starmer, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair did not stumble into the leadership of their political parties. Instead, they reached the top thanks to conniving backroom deals, secret manipulation of information known only to a few, and conspiratorial deployment of relationships with various players which might often be kept hidden.

What this shows is that in this debate over information control and secrecy, both Left and Right are currently tilting at strawmen: the Left at the spread of conspiracy, the Right at supposedly unprecedented government secrecy and authority over perceived safety. Biometric information, which is the key resource for the “BritCard”, is simply the latest tug-of-war.

This is all quite normal in politics, and distracts from the broader issues at stake. What is true is that, as Canetti observed, the impulse to assert control through a strong-arm policing of information tends to be typical of more authoritarian governments. This is what historians can observe in the absolutist dictatorships of Spain and Portugal in the era of the Inquisition, and with the trial of Crispina Peres. It is what we can now observe with the trend towards policing the internet and using it to monitor citizens. The question is not, therefore, whether governments should control information, since all governments of all time always have tried to do this: but what levels of control and secrecy are compatible with democratic life. With neither politicians nor technocrats to be entirely trusted with the levers of power, a different playing field if society is to manage the circulation of information. Perhaps the mechanism might be a combination of judicial separation of powers and sortition (election from the general public via a lottery).

At the same time, the firestorms around this topic are also a distraction from the enormity of the crisis which current governments have plunged into. Fear for the future is mounting as quickly as fury at politicians. The distraction, then, is highly useful to political elites in an age when over-reaction to threats to their control of information has caused such massive harm.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe