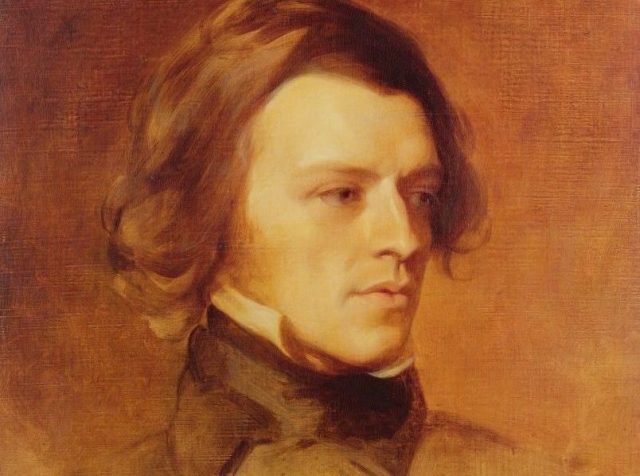

Not your typical Victorian. Culture Club via Getty Images.

“Poetry,” lamented WH Auden in his great elegy for WB Yeats, “makes nothing happen”. Rather, “It survives / In the valley of its making where executives / Would never want to tamper”. Writing on the eve of war in 1939, Auden already assumed the social irrelevance of his ancient art. No one in the West, let alone an arts “executive”, would bother to dispute that judgment now. Even in Britain, however, poetry had until recently mattered in places far beyond its own lonely ravines.

Flying high on Romantic hubris, Shelley had in 1821 claimed a role for poets as “unacknowledged legislators of the world”. In Richard Holmes’s magnificent new biography of the young Alfred Tennyson, The Boundless Deep: Young Tennyson, Science, and the Crisis of Belief, two episodes stand out as signs that, in the mid-19th century, that dream endured. Already a lionised poet, but not yet the bushy-bearded patriarch of his later decades, Tennyson learned in 1850 that one poor but avid reader in Lancashire desperately sought an edition of his verse. This was the radical activist Samuel Bamford, a survivor of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, who had been prosecuted for treason, and was now a hard-up weaver. Bamford knew Tennyson’s poems by heart but could never afford his own copy. Alerted to his plight by the Manchester novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, he arranged a personalised volume for his penurious super-fan. He told a friend: “I reckon his admiration as the highest honour I have yet received”.

A few years later, during the Crimean War in October 1854, the Light Brigade galloped in their botched suicidal charge towards the Russian guns at Balaclava. Within weeks, Tennyson had responded to the debacle with the verse that would brand him forever. “The Charge of the Light Brigade” undercuts its jingling jingoism (“Theirs not to reason why/ Theirs but to do or die”) with blistering irony.

Printed first in a liberal paper, The Examiner, the poem not only achieved near-instant if misleading fame as “a triumphant song of noble patriotism”. It quickly reached the survivors of the Charge itself in the military hospital at Scutari, on the Asian shore of Constantinople. There the wounded soldiers eagerly heard, and recited, the story of their reckless adventure before they ever read it. “Half are singing it and all want to have it in black and white,” wrote the hospital chaplain to Tennyson.

So, in the age of steam locomotives and telegraph cables, a poet in Britain might still touch and move a broad popular audience — from artisan reformers to mangled war veterans — almost in the manner of some Homeric bard. This unsought status as voice of the nation came to Tennyson relatively late, and almost by accident. The poet had feared that In Memoriam, his epoch-defining series of elegies for his friend Arthur Hallam, would outrage Christian believers with its passages of doubt and despair, and its comfortless invocation of a “Nature, red in tooth and claw”.

Instead, when finally published in 1850, In Memoriam sold 60,000 copies within weeks. Major poets today would struggle to match that figure over a lifetime. The valley of Tennyson’s verse was crowded with admirers: from working-class readers like Samuel Bamford, to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who once dropped in unannounced on the Tennysons in their Isle of Wight home to find the floor strewn with children’s toys.

Yet that very popularity helped doom the poet to a long afterlife of scorn or neglect as the booming, hirsute embodiment of outmoded “Victorian values”. The novel scientific idea of extinction — of species, cultures, and the planet itself — haunted Tennyson’s mind and work.

In the years of intellectual ferment that preceded Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859, the seemingly “savage and godless” notion that all entities, from tiny creatures to planetary systems, might die off bred a kind of “existential terror”. Holmes likens it to the dread of catastrophic climate change today. He shows that the “eternal background soundtrack of extinction” thuds like an ominous drumbeat across Tennyson’s career.

But he also wryly acknowledges that Tennyson the shaggy literary icon has pretty much gone extinct himself. Lines of his that once echoed through millions of heads in Britain and abroad do still cling on like poetic fossils. An inscription in the athletes’ village at the 2012 London Olympics quoted the closing words of “Ulysses”. In the same year, Judi Dench (as “M.”) recited in the James Bond film Skyfall the last lines of that poem, with its young writer’s astonishing empathy for the bruised defiance of old age:

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

But from “Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean” (“The Princess”) and “The woods decay, the woods decay and fall” (“Tithonus”) to the hypnotic bleakness of In Memoriam (“Break, break, break/ On thy cold grey stones, O Sea”) or the ambiguous onrush of the Charge itself (“Into the valley of death/ Rode the six hundred”), the almost eerie virtuosity of Tennyson’s verbal music has served to wrench his verses from their context. His metrical magic saves the part at the expense of the whole. Who now remembers that, for instance, the bewitching sonnet that begins “Now sleeps the crimson petal, now the white” comes from a loose, multiform satire about women’s education, “The Princess”?

Like the director of some literary Jurassic Park, Holmes recovers the DNA of this Victorian dinosaur and brings him back to roaring, striding life. Ever since his breakthrough biography — Shelley: The Pursuit, half-a-century ago in 1974 — Holmes has excelled in scraping the patina of cliché off hallowed authors and restoring to them a hot youth filled with passion, perplexity and danger. He effected the same miraculous resurrection with Coleridge (Early Visions) and Dr Johnson (Dr Johnson and Mr Savage). Later, The Age of Wonder stripped away encrusted ideas of the Romantics as wispy idle fantasists to demonstrate the poets’ deep engagement with the most advanced science of their time.

Holmes, who turns 80 later this year, writes with a zest, pace and penetration that suits his endlessly restless and curious subject. The Boundless Deep ends with Tennyson’s rapid ascent to national celebrity and the Laureateship in his 40s. Instead of the “ancient, patriarchal and prophetic” icon of familiar photos and portraits, we meet the tall, handsome, anxious son of an unstable Lincolnshire clergyman who had himself wrestled with demons of depression. A ferocious smoker and thirsty drinker, with his swarthy “Spanish” looks, strong Lincolnshire accent, and dark mane of hair, Alfred lopes through Holmes’s pages with his all precocious talent, bohemian charm, and proneness to disabling grief — above all, for his Cambridge friend Hallam, who died of a brain haemorrhage aged 22 in 1833. That loss both broke him and made him.

“The smallness and emptiness of life,” the mature Tennyson wrote, “sometimes overwhelmed me”. Holmes draws a psychic map riddled with besetting doubts and fears. They extended from the cares of his immediate family — one of Tennyson’s brothers spent most of his life confined to a Lincoln asylum, whilst two more suffered clinical-level depression — through his protracted mourning for Hallam, up to his metaphysical anxieties about an empty, mutable and pitiless cosmos. The Boundless Deep compellingly traces the triple modern challenges of “biological evolution, a godless universe, and planetary extinction” as they dig their belief-shredding claws into Tennyson’s imagination and into his verse.

Respectability, and celebrity, descended like a top hat on the former tearaway — a process regretted by his friend Edward FitzGerald, whose waspish but affectionate letters and remarks punctuate the book with a rueful commentary. Not yet the author of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, but just an eccentric gentleman-scholar, “Fitz” loved the madcap, unruly Lincolnshire lad but mocked the grand Laureate. He treated the elder Tennyson as “a Great Man lost — that is, not risen to the Greatness that was in him”.

Even after his elevation to national bard, however, Tennyson could voice a truly corrosive scepticism. To his former tutor, the trailblazing scientist William Whewell, he wrote in 1855 that “it is inconceivable that the whole universe was merely created for us who live on a third-rate planet of a third-rate sun.” If the patriotic rhymester, or the fanciful medieval storyteller of “The Lady of Shalott” won armies of readers, then so did the forlorn seeker of In Memoriam in his creative state of “hovering, or trembling, between science and religion”. As that work puts it: “There lives more faith in honest doubt / Believe me, than in half the creeds”.

Holmes recovers Tennyson “before the beard”, and the “suddenly modern magic” of his poetry, with as much acumen and energy as any writer could. All the same, The Boundless Deep left this reader fretting about potential extinction of another kind. Since his debut with Shelley, Holmes has marched in the vanguard of a glorious generation of literary biographers in Britain. With Michael Holroyd as their pioneering general (this book’s afterword salutes him as a “benign and brilliant godfather”), authors such as Holmes, Jenny Uglow, Claire Tomalin, Graham Robb and Kathryn Hughes have rescued the genre from academic obscurity and leaden hagiography. In their hands, the best literary lives merge scholarly rigour, biographical frankness, critical acuity and narrative verve to make the giants of the past breathe again.

This wave crested thanks to several overlapping trends. The postwar expansion of the humanities in higher education had swollen a graduate readership curious about such figures. So too did the revolution in book retailing spearheaded by Waterstones, and the willingness of status-conscious corporate publishers to pay generously for prestige titles. Moreover, before the internet tsunami swept away their business model, newspapers and magazines empowered by new technology had invested in cultural coverage as a route to reach that high-spending generation (call them “boomers” if you absolutely must). Combined, these forces meant that serious but lively books about past writers and artists might not just find a reputable niche, but even make a bestselling splash.

Holmes, and others, richly deserved to ride that wave. But now the tide has ebbed as far as it did on the windswept North Sea shore at Mablethorpe, where Tennyson loved to roam. Literary publishing, media and bookselling all struggle to stay afloat. Above all, the role of the humanities in British higher education has shrivelled, and will shrink much further. Those few literature students who might still encounter Tennyson would likely meet him not as a supreme master of the art of verse but just another deplorable specimen of Victorian patriarchal and imperialist ideology. And Holmes sadly notes that familiarity with “strict metrical forms” of the sort that Tennyson commanded with such bravura skill is a knowledge that has “almost been lost to twenty-first century readers”.

Here, I think, he sounds a touch too parochial. Those inclined to write off Tennyson as one more dead white dude might consider that a passionate popular interest in the exact craft of verse still flourishes in cultures where celebrity poets can fill stadiums: in Pakistan, for instance, or Iran, or perhaps the United Arab Emirates. In the UAE, a much-loved TV series called Million’s Poet draws X-Factor-sized audiences across the Arab world. It offers prizes worth around 15 million dirham (£3 million). In the Gulf, poetry can make things happen – or, at least, it can make some people rich.

Even here, perhaps, the ability to hear Tennyson’s verse as “a delicate virtuoso weave of sound magic” has not quite expired. What has withered is the faith of British elites in the value of such art. What has withered is the faith of British elites in the value of such art. In contrast, Tennyson himself received an annual Civil List pension of £200 (worth around £20,000 today) after his Cambridge friend Richard Monckton Milnes, who had become an MP, recited “Ulysses” to the prime minister, Sir Robert Peel. The Boundless Deep, and its warm reception so far, hearteningly proves that some corners of this culture continue to resist the extinction of literary memory. We still have reason to hope that the readers, publishers, booksellers (and critics) who help keep books like this alive will not go the way of the dinosaurs that stalked the poet’s unquiet mind.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe