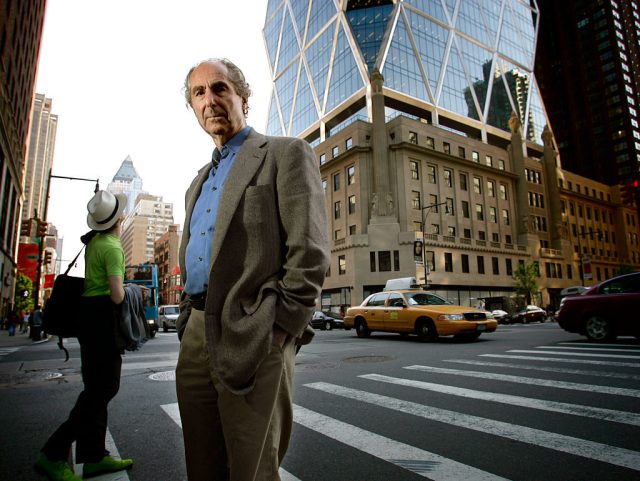

Philip Milton Roth: gleefully priapic. (Photo by Orjan F. Ellingvag/Dagbladet/Corbis via Getty Images)

In 2017, during the first wave of #MeToo, I was reluctantly noncompliant. On several occasions, I was approached by journalists to participate in stories about accused men in media, and declined to do so. As a lifelong feminist, I liked the idea of preventing powerful men from exploiting less powerful women for sex. Hence, the reluctance. Yet show trials and vicious public shaming didn’t seem like methods likely to improve society. Hence, my noncompliance.

Today’s mini-reckoning for the movement — with Harvey Weinstein back on trial, and the legal scantiness of even his morally repugnant case now impossible to ignore — suggests that I was right. So it seems like a good time to perform some more painful soul-searching about #MeToo’s deeper premises. A new piece of evidence, Canceled Lives: My Father, My Scandal, and Me, by disgraced Philip Roth biographer Blake Bailey, offers a valuable opportunity to probe the depths.

Bailey, as many will remember, was the star biographer handpicked by Roth to tell his life story. He was given the explicit direction not to sanitise any of the Portnoy’s Complaint author’s scabrous ribaldry or gleeful priapism. Bailey did as told, and the results were that biographer, author, and book were all cancelled in a scorched-earth campaign that reverberates to this day.

Roth, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998 for his masterpiece American Pastoral, was himself an early participant in the cancellation wars. One of the great themes of his later work was “how politics may serve as a mask and outlet for extra-political resentment and obsession”, as Bailey’s Phillip Roth: The Biography quotes the liberal historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. Roth observed as early as 1998 that “gossip [is] gospel, the national faith. McCarthyism is the beginning not just of serious politics, but of serious everything as entertainment to amuse the mass audience”. That same year, Roth found in the Bill Clinton impeachment a moment that allowed him to “catch a glimpse of the moral core” of “this huge unknowable country”. Sexuality was always one of his major themes, and he saw what was coming: “Feminism as the new righteousness… Women are blameless”.

Bailey’s fate was one of the stranger episodes of the cancellation era. In 2021, the publisher W. W. Norton pulled and pulped the unsold copies of the 50,000-book first printing of his authoritative 900-page Roth biography, amid allegations of misogyny and sexual assault by both writer (Bailey) and subject (Roth). The landmark work cost the publisher $575,000, had Roth’s full cooperation, and debuted at No. 12 on The New York Times bestseller list. When Norton disowned the book, indie imprint Skyhorse picked it up, making its own reputation in the bargain.

Bailey is a biographer of the highest calibre, and even at the time, some timid objections were raised to erasing a book of such cultural and historical significance due to its author’s character. The allegations, however, were ugly. A female publishing executive claimed that Bailey raped her (during a sleepover at New York Times book critic Dwight Garner’s house), and another woman who took an English class with Bailey in the eighth grade said that he’d had an inappropriate relationship with her, and had allegedly groomed her in order to manipulate her into sex as an adult. Both accusers have said they were inspired by #MeToo to come forward and hold Bailey accountable.

Bailey has written Cancelled Lives to tell his side of the story — his second such attempt. A 2022 work called Repellent was blocked by the Roth estate prior to publication, which successfully argued that some of its contents violated the terms of Bailey’s original contract as a biographer. Cancelled Lives disputes major features of his accusers’ stories — Bailey says he never had sex with the former student, and he demonstrates that the unabridged text of her emails to him tells a different story than the one she came forward with.

He also believed the sex with the publishing executive was consensual, and so on. He takes accountability for “disgustingly selfish and hurtful” behaviour regarding his then-wife, and admits to bad choices — drunk extramarital sex with a woman whose name he didn’t know at the home of an important professional contact like Garner, for example — while offering mitigating details.

Cancelled Lives transpires in terse chapters, with titles that confront the issues head-on: “Clownish Lusts”, “Our Fucked-Up Family”, “Like Father Like Son”. Bailey elegantly weaves between contemporary events and those of his childhood or his prior relationship with his main accuser. “When the first stories about my depravity began to appear, I couldn’t read them and I still can’t,” he writes. “It would be like injecting sulfuric acid into my heart and brain.” He is aware, of course, of the contents, and balances his replies to the allegations with the backstory of why he loved being a teacher, or what his involvement in his students’ lives meant to him and to many of them.

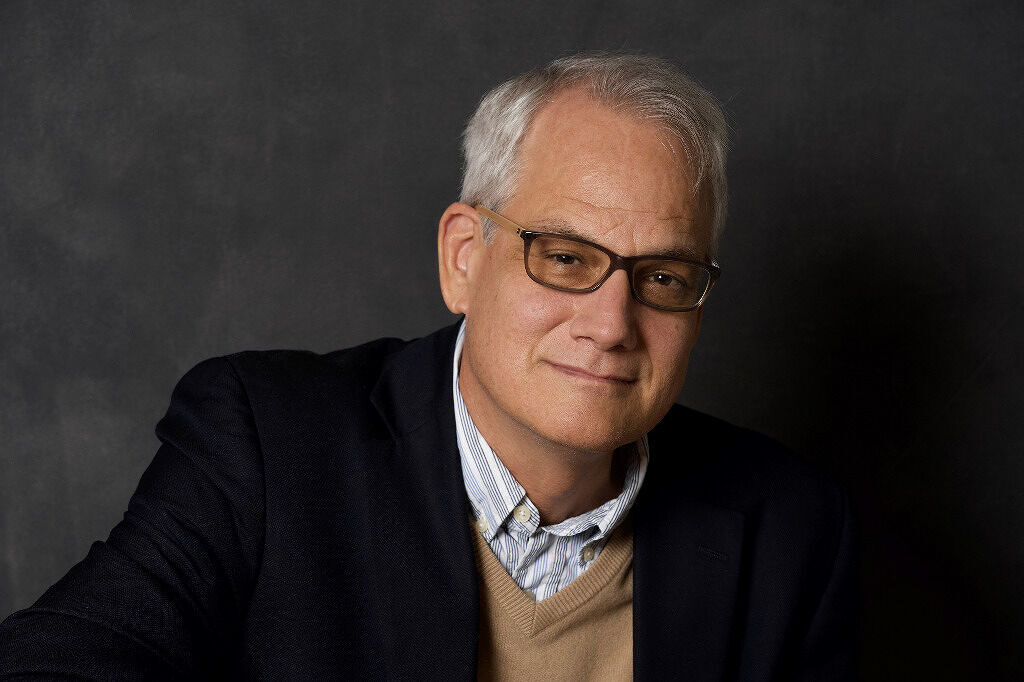

- Blake Bailey is ‘so fucking angry’. Credit: Amazon.com

His language is wisely measured in the book, but less so on the phone in an interview with me. “I’m so fucking angry”, he tells me. “The worst of what I was accused of wasn’t true. I did nothing illegal and nothing vicious. I’m not a rapist, I did not deliberately groom anybody, these were long-time friends.” Regarding the various allegations and corroboration from other former students, he says, “You have enterprising reporters calling hundreds of your former students, hundreds of the people you’ve mentioned in your acknowledgements. People, for various reasons, are eager to get their shots”.

Because he was unable to discuss the Roth material (contractually) or the dissolution of his marriage that followed his cancellation (out of respect for his ex-wife and teenage daughter), he chose to situate the story of his cancellation in the context of the next most important relationship in his life: the one with his father. Eighty-seven-year-old Burck Bailey, the other “cancelled life” of the title, was so “disturbed and heartbroken” by what had happened, Bailey says, that he went into a swift decline and died within several months of the incident. Nonetheless, his father’s support, he tells me, “was one of the reasons I decided not to kill myself”.

The personal and professional destruction inflicted upon cancelled men, and the wave of suicides that have followed, will be another matter left to the judgement of history. Bailey’s book is especially interesting, however, due to the circumstantial choice of focusing the story on his family’s male lineage, a story whose precursor he told in the 2014 memoir The Splendid Things We Planned: A Family Portrait (also subsequently pulled off the shelves by Norton).

What emerges in both memoirs is a portrait of male wreckage whose dots Bailey doesn’t quite connect, but which are suggestive to the reader, especially today, when men are in crisis by every cultural standard — health, employment, education. Bailey’s father, Burck, was a prestigious Oklahoma lawyer, who received a scholarship to the New York University School of Law, and rose to be the president of the Oklahoma Bar Association. He was “a person of renowned integrity, courtesy, intelligence, kindness and wit”, Bailey tells me.

Nonetheless, the view from Burck’s deathbed is chequered. An imprudent first marriage to Bailey’s mother ended in divorce. A second marriage resulted in estrangement from his sons. Burck’s first son, Scott, became an alcoholic and drug addict in his teens, and died by suicide, which is the main subject of Bailey’s first memoir. Bailey’s fate, of course, we all know about.

The conventional wisdom is that such men are holders of obscene privilege, and deserve their fate, whatever it may be, both the wealthy father and the two playboy sons, abusing women and crashing daddy’s Porsche, as Scott did several times in his teens. From a different view, however, the patriarchy, the institution whose monolithic control supposedly justified the dirty, by-all-means-necessary battles of #MeToo, seems to have been in decline for some time.

Bailey’s relationship with his father is easily as complicated as it was loving, and the story overall demonstrates a failure to pass on generational wealth or the father’s advantages. It seems worth noting, as well, that Philip Roth was one of the people to take a sledgehammer to these old paternalistic structures. Another of Roth’s perennial themes was the son’s struggle to free himself from the expectations of the conventional father. Roth valued the assertion of the “I” of individual authenticity against the “They” of a stultifying culture, with the penis as the tool for liberation.

One of the major criticisms of Bailey’s Roth biography, and of Bailey’s writing in general, has been his failure to sit in judgement on his subjects. He is phenomenal at revealing behavior, but less talented at drawing conclusions from it. This is a strength in biographer, but perhaps less so in a memoirist. If Roth blamed his dick for his own bad choices, Bailey let it stand. In a similar way, in The Splendid Things We Planned, he writes about his brother Scott’s struggles with addiction, depression, unemployment, and petty crime without a theory as to why it might have happened. And he’s equally in the dark as to his own situation — he details his bad choices compellingly, but sometimes openly admits he can’t explain them.

“I was not raised in an environment where sex was regarded with a great deal of moral gravity”, he says, explaining that the book’s intention was to show that this can be the case, but that you can still be a good person. The statement might be true, but it seems puzzlingly naive in his circumstances. Bailey’s next book will be a biography of the novelist James Salter, his first unauthorised work. Salter, of course, was also a man known for sexuality in his writing, a way with women, and being part of a particular boys club at a particular time — Bailey’s métier, for better or for worse, and I look forward to it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe