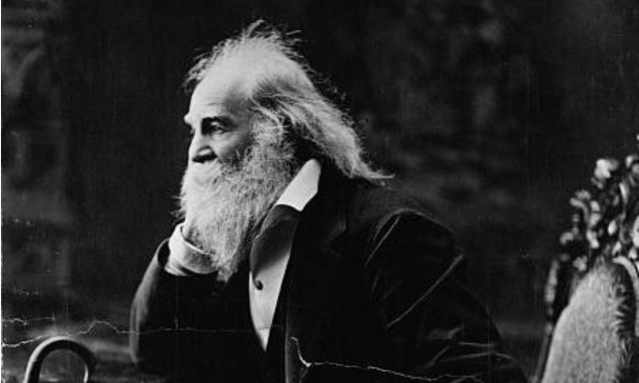

‘On closer inspection, he, uh, actually might not have been so unaided in his visions.’ Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

I can remember exactly where I was when I first read Walt Whitman. Lying on the bed in my girlfriend’s dorm room in college, I started reading “Song of Myself” from Leaves of Grass out loud and, much to my girlfriend’s annoyance, sort of couldn’t stop myself. This kind of compulsive reading had never happened to me before and never would again.

It really was as close to a religious experience as I’ve had without the use of psychedelics, and I don’t think I’ve ever entirely broken free of the spell of that moment. One of Whitman’s more ebullient contemporaries called Leaves of Grass “the Bible of America”, and that seems exactly right to me — it’s less a collection of poems and far more a religious text, a way of modelling the personality and giving full scope to one’s creativity and inner life.

More than I’m really comfortable admitting, I’ve tried to mould myself in the direction suggested by Whitman. To me that means, above all, a few things. It means treating the self as infinite: “I am large, I contain multitudes.” It means regarding the border between oneself and other consciousnesses as permeable: part of the thrill of Leaves of Grass is the whimsical way that Whitman slides into the consciousness of John Paul Jones, Davy Crockett, anybody at all really. And it means an abiding, non-negotiable sense of equality and respect towards all creation: “what is that you express in your eyes,” Whitman writes of oxen, “it seems to me more than all the print I have read in my life.”

Now that I have passed my Whitman year — “I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin” — I find myself reflecting a little more sombrely on Whitman’s vision and what it means for me. I also find myself asking the tough question — how did he do it? — since his achievement seems so simple and replicable, but no other writer that I’m aware of has ever hit quite the vibration that Whitman did. It’s a question that Whitman invites, and he is at his most teasing about it: “if you want me again look for me under your boot soles,” he writes at the conclusion of “Song of Myself”.

What we can rule out, in terms of explaining Whitman, is genius. I’ve recently read some of Whitman’s early poems, and they’re almost shocking in their banality – “Let glory diadem the mighty dead / Let monuments of brass and marble rise.” A recent cottage industry has emerged — although it might be one grad student who keeps finding all these lost Whitman works — that vastly increases our knowledge of Whitman’s early writing, but every one of these works is conspicuously lacking: none contain what Whitman called the “me myself”. And so when Ralph Waldo Emerson read the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, he wrote to Whitman of his surprise: “I rubbed my eyes a little to see if this sunbeam were no illusion.” And as Whitman biographer David S. Reynolds put it 150 years later: “A dull, imitative writer of conventional poetry and pedestrian prose in the 1840s emerged in 1855 as a marvellously innovative, experimental poet.”

There seem to be three tacks to explaining this transformation. The first is on the order of a personal epiphany, “attributed to… a mystical experience he supposedly had in the 1850s or a homosexual coming-out that allegedly liberated his imaginations”, as Reynolds writes before soberly concluding, “in the absence of reliable evidence, such explanations remain unsupported hypotheses”.

Part of what has always so stunned me about Whitman is that he managed to have the epiphanies he did without the aid of psychedelics, but on closer inspection, he, uh, actually might not have been so unaided in his visions. Calamus — the grass-like plant that plays such an important role in Whitman’s writing (a set of his poems is named after it) — turns out to possess psychoactive properties, which was known in Whitman’s time. And Whitman himself was aware of its powers. “It is a medicinal root,” he told his amanuensis in 1891, and in the same conversation appears to be aware of calamus’ ability to induce tripping. At present, calamus is rarely ingested, but looking for trip descriptions of it online, I came across the following:

“Although the effect is very subtle, my senses are more sharpened and my mind is clear… A desire to go outside and take a walk overwhelms me. I put on my shoes and walk naturally towards the forest. Here I enjoy little things that strike me: the beautiful rustling of the leaves, the wind playing with my hair, the smell of the moss. A very peaceful feeling descends over me like a blanket.”

It sounds somehow familiar.

The other piece of folklore about Whitman’s transformation involves his homosexuality, and here I have recourse to a better-documented myth about Whitman. In 1966, an intrepid researcher discovered a robust urban legend in the small Long Island town where a young Whitman had taught. Whitman had been denounced from the pulpit for pederasty, and tarred and feathered. Townspeople recalled that Whitman had “left under a cloud”, and the school would for decades after be locally referred to as the “Sodom School”.

There are some documentary reasons to doubt the story, but Whitman historians, Reynolds included, take the possibility seriously. If it’s true, and Whitman had experienced public humiliation like that on account of his sexuality, a line like “I celebrate myself” — the opening line of “Song of Myself” — sounds very different. It’s as resilient as it is triumphant, like the light in the tunnel at the end of years of therapy — it comes across as a declaration of radical self-acceptance, overcoming his angry trauma-inflected writing of the 1840s, and speaking exuberantly, at the top of his lungs.

That reading of Whitman puts him in line with the human potential movement, with microdosers and psychoanalysis patients and health nuts. Part of the cache of recently rediscovered Whitman material reveals that he wrote a book-length article series called “Manly Health and Training”, basically a highly florid men’s magazine. Whitman’s longtime boyfriend would recall that “he was an athlete — great, great. I knew him to do wonderful lifting, running, walking”.

The Whitman I’m describing here feels surprisingly contemporary and close-to-home — get in touch with your sexuality, lift some weights, find a hemp shop that sells calamus and you too can write Leaves of Grass. The second tack on Whitman makes him a little more remote. That would be to link him with a particular moment in the development of American national consciousness. Whitman was maybe the most conspicuously patriotic of major poets and he explicitly linked his writing to the expansion of the United States. “The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature,” he wrote in the preface to the Leaves of Grass. “The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.” We can understand this in two ways — one is that American English, in Whitman’s time, was a sort of fresh clay out of which a new literature could be moulded, much as Shakespeare in the 1590s or Pushkin in the 1820s had a sort of first-mover advantage with their respective literary languages. Or we can understand this as meaning that Whitman had a messianic vision distinctive to America — that American democracy and exuberance would produce what Whitman calls “a copious, sane, gigantic offspring”, a living poem replete with “perfect characters and perfect sociologies”.

It is this vision that, for us now, leaves a bitter aftertaste. Of all Whitman’s characterisations, “sane” is the hardest to apply to our particular moment of American history. Whitman did seem to anticipate that his idea of America might be overly optimistic. In the otherwise exuberant Democratic Vistas, he writes: “the United States are destined either to surmount the gorgeous history of feudalism, or else prove the most tremendous failure of time.” And it’s that tremendous failure that, in the year of our Whitman 170, I find myself grappling with — that America just failed to achieve its potential, never acquired a real maturity and then, eventually, lost its idealism. Whitman, in the closest he would get to standard-issue political critique, wrote: “the fear of conflicting and irreconcilable interiors, and the lack of a common skeleton, knitting all close, continually haunts me.”

But it’s the third tack to understanding Whitman which actually may be the most relevant and direct lesson of Whitman’s. What Emerson called “the long foreground” of Whitman’s was mostly journalism and self-publishing. Whitman, who left school at age 11, trained as a printer’s devil. And, throughout his career, he was intimately tied (in a way that very few writers are) to the physical production of his own work. He worked as a typesetter for publications in New York, founded his own newspaper The Long Islander, and for two years was the editor of the well-known Brooklyn Eagle. What he mostly was, though, was a failure. The self-publishing didn’t earn much. His practical-minded brother George would lament that “he made nothing of his chance” during the “great boom in Brooklyn” in the 1850s. And Whitman, who seems to have been living rough as much by necessity as poetic persona, would in 1840 style himself as part of a “loafer kingdom”.

But it was Whitman’s outsiderness — combined with his willingness to take control over the means of production — that accounted for his literary miracle. High-brow American literature in Whitman’s time was awful, really awful — stale hand-me-downs of European prosody — and Whitman, too, struggled to break free of it. “I too, like all others, was born in the vesture of this false notion of literature,” he said late in life. But he did break free of it. He came across enough fresh influences — Martin Tupper, Emerson himself — that he was able to develop a more distinctively American sensibility, augmented with the language of the streets and a dash of the pulpy writing emerging from the nascent penny presses. And by 1855, he was able to take care of the publication of Leaves of Grass entirely by himself — writing parts of the famous preface directly onto the keys of the press in the print shop, and then handling his own advertising and distribution.

What Whitman was doing sounds, of course, very much like blogging or Substack — and I have no doubt that if he were alive today that’s exactly how he would be distributing his work. In an excitable mood, I wrote on my Substack recently that “what we’re really on the cusp of is a whole different way of being”, and what I meant was the capacity of the internet to eliminate gatekeepers and to open the way for the “new, superb democratic literature” that Whitman described. This statement of mine was met with some skepticism. If Emerson “rubbed his eyes a little” at Leaves of Grass, the Substacker Teddy Brown had to “close [his] eyes and rub [his] temples” at the sheer stupidity of what I was saying.

But I stand by it. In one of his more mysterious poems, “The Song of the Answerer”, Whitman describes a figure maybe a century or five centuries in the future who will be his poetic analogue. I had always taken the Answerer to be a kind of Messiah, a Mahdi of lyric poetry, who would provide the “answers” to the poetic questions that Whitman posed. But rereading the poem now, and meditating on the superhuman qualities of the Answerer it occurs to me that Whitman isn’t describing a person but a spirit. What it is is a profound sense of equality: of a mutual respect that extends from mechanics to soldiers to sailors to authors to artists to labourers to gentlemen to prostitutes to beggars to congressmen.

The exuberant, expansive, athletic America of Whitman’s era may be long gone — if it ever really existed — but the vision of the Answerer isn’t as remote as Whitman sometimes makes it seem. It is, simply, a democratic sensibility. To find it requires at the same time, paradoxically, immense humility and a nearly boundless confidence. As Whitman put it, “There was never any more inception than there is now,” and the vision of the Answerer requires little else than a reaching for it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe