‘The effect is to drive prices higher. And higher. And higher.’ (John van Hasselt/Sygma via Getty Images)

It is, perhaps, the most vexing paradox of the modern American economy. The median household income, adjusted for inflation, has risen by over 30% in the last four decades — and yet the average American family can barely afford to buy a nice home, to send the kids to university, to access high quality health care.

How can this be? The economist Arnold Kling has a theory, and it’s a doozie. If he’s right, then decades of domestic public policy have been misguided.

The unfortunate truth is that Democrats and Republicans alike, under the cover of good intentions, have been passing laws that undermine the economic well-being of American families. Even more disturbing, these policies have created a whole new class of robber barons, who rely on government policy to enrich themselves. But these new robber barons aren’t railroad tycoons or rapacious oil companies. Indeed, many of them are non-profits: they include universities and hospitals, drug companies, insurance companies, K-12 school districts, and real estate investors.

What is Kling’s theory? In key sectors of the economy, he says, the US government has been, first, restricting supply and, second, subsidising demand. The effect of both is to drive prices higher. And higher. And higher.

This is how it works: Claiming to be the guardian of “quality”, policymakers put up barriers to entry, making it extremely costly, for example, to launch a new university or hospital. This is the restriction of supply. At the same time, in the name of “helping” consumers, they push billions of dollars into student loans or healthcare payments. This is the subsidisation of demand.

Kling, a former economist at the Federal Reserve, first wrote about this phenomenon in his 2016 book Specialization and Trade. “The politics are always going to push in this direction,” he told me recently.

The great irony is that the vast bulk of the subsidies end up in the hands of providers, not consumers. These service providers are the new robber barons. Look closely, for a moment, at the latest student loan bailout. Last month, President Biden announced that $6.1 billion in loans would be forgiven for former students of the Art Institutes, a shuttered scam university that had been forced to pay a legal settlement of $95 million for fraudulent recruitment practices.

It’s easy to blame the students here. It probably wasn’t so savvy to take out tens of thousands of dollars in loans for art degrees that were probably worthless. But that’s a key point, isn’t it? If the degrees are worthless, then the students didn’t really walk away with the government’s $6.1 billion.

Who did take it? The former owners of the Art Institutes. The company eventually went bankrupt, but prior owners effectively stole $6.1 billion in taxpayer money (actually, probably about twice that), and all they had to do was pay $95 million in fines to various government agencies that sued them, including the US Department of Justice.

It would be quaint to think of this as a for-profit education scandal. Quaint, but wrong. For ultimately, all of the universities, including elite colleges in the Ivy League, have reaped billions of dollars in economic rents — excess profits — from student loan programmes, even as the value of many of their degrees has fallen dramatically.

At the same time, the universities operate an accreditation system which makes it extraordinarily difficult and costly to launch a new university that might compete with them. In fact, you usually can’t get your new university accredited until four-to-six years after you open. That means that your first students aren’t eligible for federal student loans — their subsidies — until you get your accreditation. It’s a huge handicap for anyone who wants to disrupt the current oligopoly of higher education.

These dynamics play out in all of the most important sectors of our economy. In healthcare, new hospitals in many states have to apply for a “certificate of need”. Often that certificate has to be signed by the other hospitals in the area — in other words, their potential competitors. Meanwhile, federal and state governments flood the healthcare system with subsidies that increase demand and drive prices up: almost 50% of health care spending comes from governmental entities in the US.

In housing, similarly, we restrict supply by making it harder and harder to build new units, especially in city centres where demand is the highest. Meanwhile, we subsidise demand by providing government-guaranteed mortgages and by offering huge tax breaks for anyone who purchases real estate, especially investors.

And in K-12 education, school districts around the country are trying to stamp out charter schools, which increase supply, while at the same time arguing for higher and higher per-pupil spending. The cost to educate one child for one year has increased 173% (adjusted for inflation) since 1970, and half the kids still can’t read.

The pathologies of these sectors all follow similar patterns. Politicians proclaim their desire to “protect” quality and “help” consumers. Industry lobbyists step up to write bills that restrict supply and subsidise demand. Prices go up. Providers become more and more reliant on the government for their profits. Consumers become more and more reliant on the government to afford homes, healthcare, and schools. Instead of investing in innovation, providers spend their money on political donations and lobbyists. Politicians become dependent on those donations. Consumers demand more and more help because prices are going up, and they’re getting ripped off. And the beat goes on. “It really is a self-reinforcing process,” says Kling. “People don’t understand that the subsidies drive up prices, so they keep demanding more.”

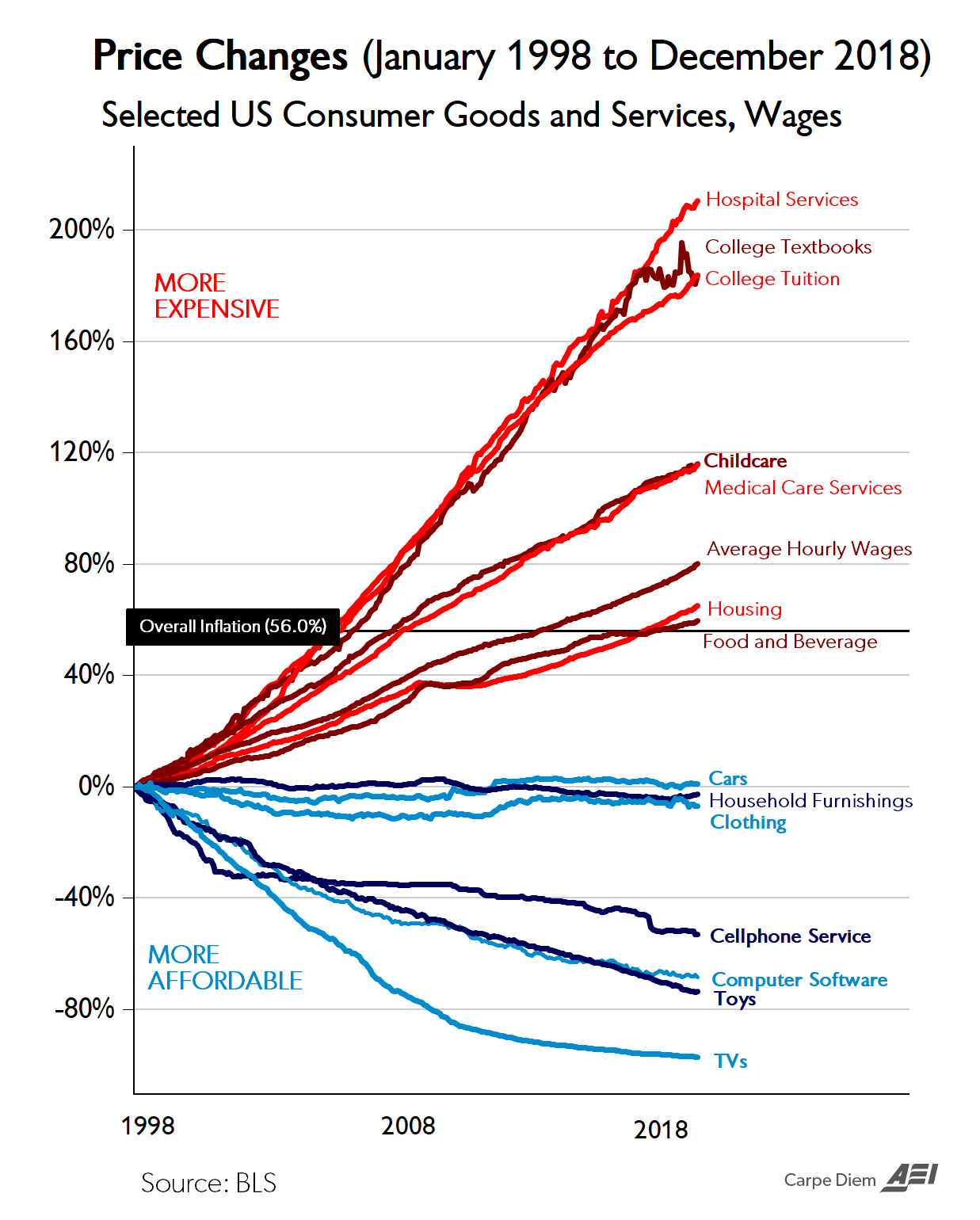

In a 2020 book, I called this phenomenon the Bleeding Heart & the Robber Baron, because it represents a political alliance between the compassionate and the greedy. It goes a long way toward explaining so much of what is wrong with American public policy and the economy. It also explains what Bloomberg has called the “chart of the century”. Below is economist Mark Perry’s infamous inflation chart, showing that certain sectors of the economy have seen dramatic inflation in recent decades, even while other sectors have seen prices decline.

The top seven components of CPI — all of them in the Bleeding Heart sectors of education, health, and housing — have seen inflation of 56-210% over the last 25 years. Meanwhile, almost all of the other sectors have seen prices remain flat or even decline by up to 90%.

Using Kling’s insights, the tech investor Marc Andreessen has labelled these Bleeding Heart sectors as the “slow” sectors. According to Andreessen, the reliance on government largesse leads to “slower productivity growth, slow adoption of new technologies… and then as a consequence of all of that, rising prices”.

Tragically, neither party wants to talk about this. Both Democrats and Republicans have participated in — and benefitted from — this new age of Robber Barons. Democrats fight new housing in the cities; they forgive student debt; they subsidise the consumption of health insurance and healthcare. Republicans, meanwhile, support big tax breaks for real=estate investors; they pass huge entitlement programmes that subsidise the purchase of subscription drugs; they back the privatisation of giant lending companies that enjoy de facto government guarantees and therefore dominate the mortgage market.

The biggest barrier to change will be those who benefit from the current policies, as many of us are addicted to one or more of these revenue streams. Providers, the modern-day Robber Barons, will resist any efforts to shut off the spigot of public subsidies. They will also fight any efforts to allow their competitors onto a level playing field. And understandably, the average American will be reluctant to give up his or her subsidies until the prices start to return to a normal level. “I wouldn’t describe the economy as addicted to it,” says Kling. “The economy would be fine if all of it went away. But I think the political system is addicted to it.” It’s not going to be easy, but the first step for any addict is admitting that you have a problem. And Arnold Kling is telling us the truth about our problem.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe