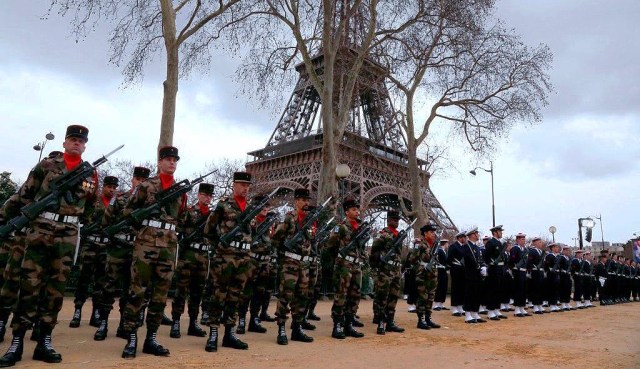

A ceremony in memory to the victims of the Algerian War of Independence. Credit: FRANCOIS GUILLOT/AFP via Getty Images

Algeria haunts France as Ireland haunts Britain. The spectres of its history have proved just as hard, or harder, to confront. Imagine, for example, that the Bloody Sunday killings of January 1972 had taken place not in Derry but around Parliament Square. Imagine that armed security forces had killed not 14 peaceful protestors but an estimated 200. Imagine that many bodies were then dumped into the Thames from Westminster Bridge. Imagine, too, that this state atrocity had been dropped into a pit of denial that lasted for half a century. And that a British leader’s eventual, modest admission that these events had been “inexcusable” still provoked howls of outrage.

The massacre of Algerian demonstrators by police in central Paris on 17 October 1961, and its decades-long cover-up, burns all those who touch it. This October, on its 60th anniversary, President Macron’s guarded avowal that the killings represented a “crime” unleashed the wrath of Marine Le Pen and other nationalists. Since then, it is the Right-wing maverick Éric Zemmour, who comes from an Algerian Jewish family, who has set the tone for next spring’s presidential election — even if his candidacy fails, as it will.

Millions of French people, like Zemmour, descend directly or have close links to the pieds-noirs: European Algerians who resettled in France after the brutal independence war led to French withdrawal in 1962. Millions more belong to Arab and Berber families with Algerian roots. The intimacy and intensity of this almost-domestic quarrel explains much about the country’s recent politics.

In 1954, when anti-colonial revolutionaries of the FLN began hostilities, Algeria became an early example of those causes that, in the age of mass media, polarise opinion not just in their own backyard, but among rival tribes of impassioned onlookers. As French paratroopers routinely turned whips and blowtorches on suspects plucked from the Casbah of Algiers, as settler militias murdered their Muslim neighbours, and as FLN guerrillas executed “traitors” by the score and planted bombs in cafés packed with European families, the now-familiar rhetoric of “With-us-or-against-us” and “Whose side are you on?” carved its acid path through a worldwide language of partisanship and recrimination. There it remains, its corrosive power massively enhanced by social media, which has glamorised the fury of the bystander — the vicarious passion that drives so many battles for the moral-political high ground that spill over their original borders.

For that reason, the tormented but always-lucid responses of Albert Camus to the agonies of his native land have lost none of their vigour and value. Famously, Camus chose not to choose between the commitments of his Arab and his European friends. He detested racial and social inequality, the “institutional” abuses of colonialism (his adjective), and the laws that enforced them. He demanded democracy and self-determination for all Algerians in a federation of free peoples. But he opposed formal rupture with France, and stoutly defended the rights of European Algerians to flourish in the only homeland they had ever known. For Camus, all Algeria’s peoples “must live together where history has placed them, at a crossroads of commerce and civilisations”.

When his refusal to share the “bitterness and hatred” of either settlers or revolutionaries isolated him, he fell silent on the subject closest to his heart and mind for well over two years. “I have passionately loved this country, in which I was born and from which I have taken everything I am,” he said in his final public statement in Algiers in 1956, “and among my friends who live here I have never distinguished by race”.

Camus was the impoverished Algiers-born child of a father who (in his infancy) died on the Western Front, and a deaf, illiterate mother who cleaned houses. He could never conceive of himself and his working-class peers as part of an oppressive colonial elite. He could, and from an early age did, not only recognise but fight against the racially-coded injustices of French rule. Indeed, his outspoken 1939 reports on famine and hardship in the Kabylia region for the Alger républicain newspaper got him blacklisted by the colonial authorities, and prompted his move to France.

However, his great works of fiction in the 1940s — first L’Étranger and then La Peste — quickly attracted not just acclaim but doubtful scrutiny. Critical readers argued that they masked or dodged the realities of the Algeria he so loved: in the unspeaking anonymity of the “Arab” gratuitously killed by Meursault in L’Étranger; or in the sidestep into allegory undertaken when Camus depicts pestilence raging in Oran in La Peste. Later critics, from Conor Cruise O’Brien and Edward Said to the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud — who in 2013 brilliantly rewrote L’Étranger from the perspective of the victim’s family in his novel The Meursault Investigation — have found large, non-European elements of Camus’s native land “of happiness, energy, and creativity” missing in the stories that he told about it.

In his essays, public statements and journalism, however, Camus lays bare the internal divisions that tore his pied-noir soul in two. A new Penguin Modern Classics collection of speeches and lectures, Speaking Out, collects interventions on the burning topics of his day: from post-Second World War cultural despair, to the them-and-us blind loyalties of the emergent Cold War; from the obscenity of state violence against workers’ uprisings in the Communist countries of eastern Europe, to the growing respectability — which disgusted Camus, whose mother had Spanish origins — of Franco’s still-vicious dictatorship in Spain.

It also contains his remarkable “Appeal for a Civilian Truce in Algeria”, delivered in Algiers in January 1956. When it came to the future of his birthplace, Camus did not so much sit on the fence as dance naked in no-man’s-land. Exposed to raking fire from every side, he spoke with the almost-naive courage that had carried him through the war as a Resistance activist and editor of the underground journal, Combat.

His “Appeal for a Civilian Truce” is the classic testimony of an embattled pluralist who will resist political and ethnic tribalism to his last breath. Camus looks on aghast at the “fratricidal struggle” that has locked “the two peoples I love” — European and Arab Algerians — “in mortal combat”. For him, “The endless dispute over who committed the first wrong becomes meaningless”. He appeals beyond militants and partisans to a wider “community of hope” that embraces diversity. Camus re-states his faith “in differences, not uniformity, because differences are the roots without which the tree of liberty withers and the sap of creation and civilisation dries up.”

Camus well knew how deeply rancour and suspicion suffused both camps. He asked, for the moment, not for any cessation of hostilities; merely a promise by combatants not to target civilians with terror or reprisals, because “no cause justifies the deaths of innocent people”. As he spoke, in the hall of the Arab-owned Cercle du Progrès in Algiers, diehard settlers heckled him. Outside, a large crowd of angry demonstrators brandished placards demanding “Death to Camus”. At this stage, though, Camus still enjoyed protection from the FLN. One of their more conciliatory leaders — his old friend Ferhat Abbas — later joined him on the platform.

But the FLN did not listen; neither did the militant settlers; still less the French army. The round of atrocity and counter-atrocity — what Camus elsewhere calls “the bloody marriage of terror and repression” — rose into a spiral of ever-intensifying savagery. Even independence in 1962 failed to stem it: thousands of harkis, Algerians who had fought with the French, were slaughtered, along with their families, after the colonial administration packed its bags.

Distraught and despairing, Camus said and wrote nothing on Algeria between early 1956 and mid-1958, when he collected his articles and speeches into a book. Behind the scenes, he interceded with French ministers to show leniency to Algerian fighters sentenced to the guillotine. By 1958, however, no one in a with-us-or-against-us climate of mutual detestation wanted to hear from the sad guy in the middle of the road. The publication flopped; and it took until 2013 for these Algerian Chronicles to appear in Arthur Goldhammer’s first-rate English translation. It remains an exemplary, even inspiring, act of conscience and of witness.

Camus’s Algerian dilemmas had nothing to do with “centrism”, with compromise or with even-handed detachment. He knew, he loved, and he suffered with, both irreconcilable sides. Riven to the core of his being by divided allegiances, Camus the Algerian appears, in hindsight, to be as much of a tragic figure as any of the existential heroes he created in works such as The Fall or The Just. Posterity, and reputation, has sometimes blunted the force of the wrenching ambivalence that he felt about his homeland and its fate. Read his own words and this conflicted integrity comes into dazzling focus.

In 1957 — as Algerian Chronicles though not Speaking Out explains – Camus ran into trouble after he had travelled to Stockholm to accept the Nobel Prize. At a press conference the next day, an FLN journalist attacked his stance. Camus responded by reaffirming his belief in “a just Algeria in which both populations must live in peace and equality”. But he also condemned “blind terrorism” in Algiers. “People are now planting bombs in the tramways of Algiers,” he said. “My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother”.

Le Monde, however, reported a twisted paraphrase of what he had said: “I believe in justice, but I will defend my mother before justice.” Worse, a grossly distorted version of his meaning passed into political folklore when later writers pretended Camus had stated: “Between justice and my mother, I choose my mother.” Yet the thrust of his remark was to show that indiscriminate violence against civilians never counts as “justice”. Divided souls, even one as eloquent as Camus, may struggle to get their message of balance, nuance and plurality across. Now, in another age of fervent faith and monocular vision, we need to hear it again.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe