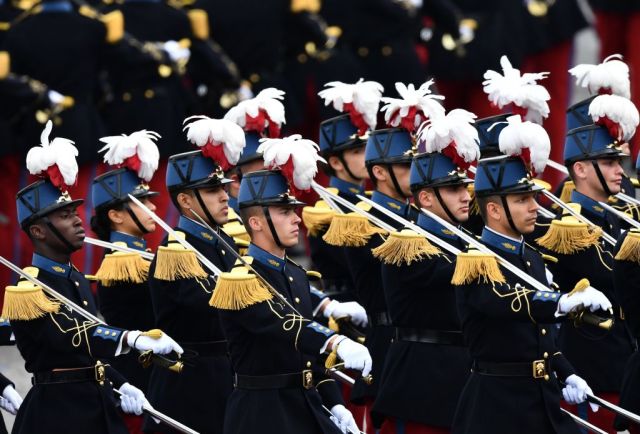

PARIS, FRANCE – JULY 14: French soldiers march during the annual Bastille Day military parade in Paris, France on July 14, 2019. (Photo by Mustafa Yalcin/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

The recent deaths of two notable anciens combattants of the French Resistance tell us much about the soul of France. Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who died aged 94, was the Grand Old Man of French politics: suave and aristocratic in demeanour (he claimed to be descended from Louis XV), and a figure who brought a certain regal hauteur to the French presidency in the 1970s — although to British comedians his name sounded like the twanging of knicker elastic, perhaps appropriately given his notorious eye for the ladies.

Like so many French politicians of his generation, he had been a resistance fighter and then a highly decorated army officer. He had participated in the liberation of Paris, so his intimate funeral mass in the country church at Authon — albeit one presided over by the Bishop of Blois — felt like the end of an era in French history.

But it was the secular obsequies a week earlier in Paris for another famous figure, Daniel Cordier, that captured the world’s imagination. Cordier, who died aged 100, had been the secretary to Jean Moulin, the First President of the National Council of the Resistance who suffered death by torture at the hands of Klaus Barbie, “the butcher of Lyon”, in 1943. Cordier had a fierce patriotism that evolved from a youthful interest in reactionary royalist politics into disgust with Pétain’s surrender in 1940. Three days after the capitulation, Cordier left France to join up with other Free Frenchmen to continue the fight against fascism. By 1942 he was parachuting into Montluçon as an intelligence operative of the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action.

Cordier was afforded a full state funeral in Paris with both Presidents Macron and Hollande in attendance. The location for the ceremony was amid the austere grandeur of the cour d’honneur in Les Invalides, the setting for great moments in French history from the revolutions of 1789, to the unjust degradation (and subsequent rehabilitation) of Alfred Dreyfus, and the full state honours for that selfless officer of gendarmes, Lieutenant Colonel Arnaud Beltrame.

Under an unsmiling bronze statue of Napoleon (itself made from Russian and Austrian guns captured at Austerlitz), a grand republican liturgy was conducted with Macron as the chief celebrant. To the slow beat of the black-clad-drums of the Garde Republicaine, Cordier’s tricoleur-draped coffin was borne into the square by ten officer cadets of the St Cyr Military Academy, whose vivid Second Empire uniforms and pantalon rouge recalled the glories of the army of Napoleon III, from the Malakoff to Solferino, and the countless fallen of Guise, and the Marne in 1914, when officers “thought it chic to die in white gloves”.

In fact, the whole spectacle — and the nearby tombs of Turenne, Bugeaud, Foch and Leclerc — is a rebuke to the tedious Anglocentric view that French military history is merely a litany of defeats. The deeds of Cordier and his confrères in redeeming the ignominy of 1940 are a refutation of that calumny alone. As was the record of those who fought under the Cross of Lorraine, from Bir Hakeim and Monte Cassino to the French First Army that crossed the both the Rhine (capturing Karlsruhe and Stuttgart) and then the Danube in 1945.

So too was the presence among Cordier’s mourners of the Chief of the French General Staff, François Lecointre — the man who led the French Army’s last bayonet charge when his unit cleared a bridge of Bosnian Serbs in 1995 — a reminder of the depth of the Gallic martial tradition, and France’s enduring role as a formidable military power.

Emmanuel Macron is clearly a frustrated thespian (he even married his former drama teacher), but he was born for moments like this. In a touching eulogy — in which he seemed to implicitly link the death of an anti-fascist like Cordier with what he has described as the need to defend the Enlightenment in a ‘struggle against barbarity and obscurantism’ — he remarked that Cordier was a man “with a taste for action and impetuous bravery”, whose life was “an adventure novel”, who nonetheless “always acted out of love: the love of freedom which justifies taking all risks; the love of beauty which led him to revere so many artists; the love of truth that made him write history”.

But the most moving part of the ceremony came next when Macron, usually so loquacious, stood in dignified silence by the coffin as the French Army choir sang the “Chant des Partisans”, the great anthem of the Resistance.

Much like the startlingly homicidal verses of the Marseillaise itself — with all those references to blood-stained flags, cutting throats and watering the fields with (yet more) impure blood — the Partisans’ hymn is similarly sanguinary, including a call to “kill swiftly” with bullet and knife, and picturing “black blood drying on the roads under the sun”. And yet the moving line in the last verse ami, si tu tombes, un ami sort de l’ombre à ta place (“mate, if you go down, another one from the shadows takes your place”) speaks to the enduring power of liberté, égalité, fraternité.

As affecting as these lyrics are, there was something too about the unmistakably French faces of the choir, their beautifully precise diction, and the resonance of their voices amid those timeless surroundings that made their performance so emotionally powerful; a force multiplied still further as the camera kept cutting to an old man in a Foreign Legion green beret, sat in a wheelchair, seemingly lost in contemplation. He was the 100-year-old Hubert Germain — Cordier’s comrade and the last of the Companions of the Resistance.

All of this captures something unmistakenly, and touchingly, Gallic. When the British War correspondent Wynford Vaughan-Thomas was attached to the French First Army in 1944 their advance became bogged down on the edge of the famous wine country of Burgundy. Wondering what was wrong, Vaughan-Thomas hastened to the army headquarters to find anxious staff officers pouring over maps, clearly worried that their advance would destroy some of the greatest wineries in the world.

“At that moment a young sous-lieutenant arrived and said, ‘Courage, my generals — I’ve found the weak spots of the German defences: every one is in a vineyard of inferior quality.’ The general made up his mind at once: ‘j’attaque!'”

Like Charles de Gaulle, it is common to hold “a certain idea of France”. Such ideas might be idealistic and romantic, and yet despite our historical rivalry, so many British people are still beguiled by these stories of French culture and French courage. After watching the poignant funeral of Daniel Cordier, many of us might be moved to agree with Thomas Jefferson that “pour tout homme, le premier pays est sa patrie et le second c’est la France”.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe