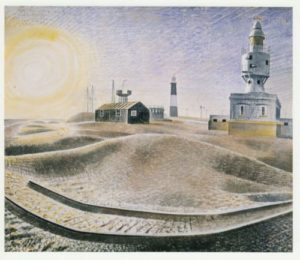

Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway passing the lighthouse at Dungeness. Credit: SSPL/Getty Images

Looking south from my childhood bedroom, the horizon was never dark, even on the gloomiest of nights in the depths of winter. Even during power cuts, which seemed to occur much more often than they do now, the row of bright lights remained undimmed. They belonged to the two nuclear power stations that stand on the coast at Dungeness.

Dungeness is an odd sort of place, to put it mildly. To get a sense of what it is like, think of an artists’ community in a near-desert of shingle, consisting of houses built from driftwood and old train carriages, all on a storm-battered headland in Kent, with a globally unique ecosystem, a tiny steam railway, and of course those two gigantic nuclear plants dominating the view to the south.

Its remoteness and unique atmosphere has proved irresistible to artists, most famously the film director Derek Jarman, who moved to a cottage there after falling ill with AIDS in the 1980s. One of my favourite painters, Eric Ravilious, executed a striking picture of the old lighthouse in 1939. The year after that, Dungeness Point was the scene of a darkly comic vignette of wartime history: two Nazi spies who were landed there blew their cover by attempting to buy alcohol before noon at a pub in nearby Lydd, and were later hanged.

Had there not been a war on, it is easy to imagine that the landlady who reported Herr Meier and Herr Waldberg might not have been such a stickler. Romney Marsh, of which Dungeness forms the southern boundary, had for many years the reputation of a place where the law’s writ ran a little unevenly.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries smuggling was rife. It is one of the closest points to the continent on the whole English coast, conveniently furnished with numerous gently sloping beaches, and in past centuries was inaccessible and hard to navigate for the stranger. Rudyard Kipling, who lived not far away, at Burwash on the Sussex Weald, contributed to the image of the Kentish smugglers as charming rogues with his famous poem ‘A Smuggler’s Song’:

“Five and twenty ponies,

Trotting through the dark —

Brandy for the Parson, ‘Baccy for the Clerk.

Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie —

Watch the wall my darling while the Gentlemen go by!”

Another builder of the romantic legends was the author Russell Thorndike. He wrote the Dr Syn series, splendidly preposterous old-fashioned swashbucklers about a mild-mannered Church of England cleric, the Vicar of Dymchurch, who moonlights as The Scarecrow, feared chief of a gang of smugglers. They lead the Revenue a merry dance over the course of seven novels. I was introduced to the books by my father, who is himself a mild-mannered Church of England cleric living on Romney Marsh, but not as far as I am aware a notorious brandy smuggler.

People who have heard of the Marsh are often familiar with its two most famous institutions. Firstly, the Romney breed of sheep, which is now farmed all over the world, from South America to New Zealand, where it makes up more than half of that country’s 40 million-strong flock.

And secondly, the narrow-gauge Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway, the 1920s brainchild of millionaire enthusiasts Captain Howey and Count Louis Zborowski, and now a popular attraction for tourists from all over the world. Its fame has spread considerably — there is a Shuzenji Romney Railway in Japan, closely modelled on its English namesake. During the Second World War, a special armoured train ran on the railway’s line, acting as a sort of mobile anti-aircraft unit; it scored only one success, but certainly looked good in propaganda newsreels. Indeed, the entire line was taken over for military purposes, which was hardly surprising given that the enemy lay less than 30 miles away.

The proximity of Europe has been pivotal in the Marsh’s history. Those original continental troublemakers the Romans had a port at Lympne, a village which now lies some distance from the shore following the retreat of the coastline. You will still occasionally hear the chauvinistic local legend that William the Conqueror initially attempted to land near New Romney, but was seen off by the hardy locals, and only then tried his luck further west at Pevensey, where he made his successful landing against the (by implication) soft and irresolute Sussex men. The tale has a kernel of truth: it seems that some of the Bastard’s men did disembark at New Romney by mistake and were rebuffed, but it was a small scale engagement.

Long after the ructions caused by the Normans, the French continued to be a source of unquiet, as well as informal duty-free booze, on the Marsh. From 1800, the coast was heavily fortified against a feared Napoleonic invasion, with the building of the Royal Military Canal at the foot of the surrounding hills to delay any invading French army, and a chain of small gun-emplacements called Martello towers, alongside larger forts at Dungeness and Hythe. Later, the district was expected to be one of the sites for a Nazi invasion; inspection of captured plans after the war confirmed that this had indeed been the enemy’s intention. The field next to my parents’ house contains a concrete bunker dating from this time, presumably intended to defend the road into town from the beach.

Romney Marsh is not nowadays marshland as most people would imagine it. There is no great Grimpen Mire waiting to entrap the incautious traveller, and no squelching bog. For some centuries, most of the Marsh has been grazing pasture. This has not always been the case: well into the second millennium AD, what is now the Marsh was a mix of shallow tidal lagoon and true marshland, with the River Rother snaking through the southern parts.

The lay of the land was radically altered by a series of fierce Channel storms in the second half of the thirteenth century, culminating in the notorious Great Storm of 1287. Old Winchelsea, a substantial place with an estimated population in the thousands, was entirely obliterated and most of the island on which it stood submerged, Atlantis-like, by the surging sea. The modern town of Winchelsea, founded by the survivors of this event, stands on top of a hill: they weren’t taking any chances (although their eventful history wasn’t over — Winchelsea suffered French and Spanish raids during the Hundred Years War and was burned by the French in 1360).

The aftermath of the Great Storm was tough for the place in which I grew up, New Romney. Not only was it severely damaged but, having been a thriving port at the mouth of the Rother, the town’s economic fortunes also declined rapidly after 1287, as the course of the river had shifted well to the south, rendering the harbour useless. Whether the storm itself was directly to blame, as local folk history suggests, or whether the lower Rother and the harbour had become gradually choked with silt and shingle over many decades, and the storm was simply the last straw, the town became something of a backwater.

The fluctuating shape and extent of the Marsh, and changing patterns of land use, have resulted in numerous once thriving communities being abandoned. Within a day’s walk of my parents’ house, there are at least four ruined churches situated far from any modern settlements. One such example is the dramatic All Saints, which served the long-extinct parish of Hope.

Not all these lost communities vanished as suddenly and dramatically as Old Winchelsea. Broomhill, close to Dungeness, gradually became uninhabitable due to the encroachment of the sea in late medieval times. Many villages and hamlets were badly affected by the Black Death or by the malaria which seems to have lingered well into the eighteenth century.

Other relics reflect the more recent past. Close to the trackbed of the partially dismantled Appledore-New Romney branch line, a casualty of the Beeching Terror — the rails remain in place as far as Dungeness, for the sole purpose of transporting spent nuclear fuel — stand three very strange concrete structures. One is a large convex vertical wall, measuring about 200 feet from end to end. The other two resemble giant satellite dishes, set in sturdy stone bases. One is about 30 feet in diameter, the other about 20 feet. They are acoustic mirrors, the legacy of interwar experiments with creating an early-warning system for enemy aircraft crossing the Channel. Similar installations survive at Hythe, and on the cliffs near Dover, but they were never used in anger, having been superseded by radar by the mid-1930s.

The mirrors contribute to the somewhat eerie beauty of the Marsh, with its long unimpeded views and big skies. Perhaps too the precariousness of the Marsh’s existence adds a certain drama and savour to the contemplation of its landscape. After all, most of the land between the Royal Military Canal and the Channel is at or below sea-level: everyone who lives on the Marsh depends on the coastal defences. In the Dr Syn books, Russell Thorndike quotes a fictional though highly apt motto for the Marshfolk: “Serve God, honour the King, but first maintain the Wall.”

It’s hard not to draw lessons for what we might think of as our uniquely modern dilemmas: the inescapability of some kind of entanglement with our European neighbours, however secure we may feel in our island redoubt; the imperative for humility and flexibility in our dealings with the inexorable forces of nature; and the need to accept inevitable change to maintain the broad shape of a way of life.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe