Artwork by Krieg Barrie

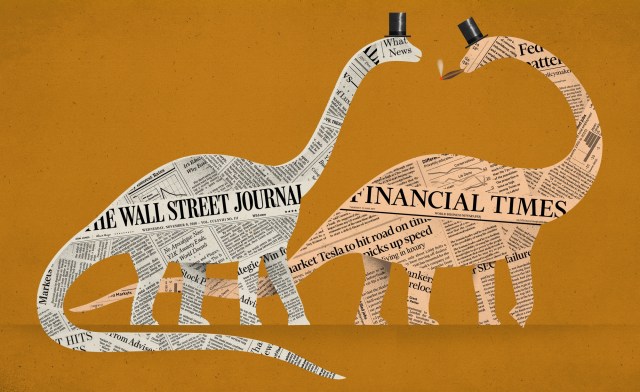

The first in a series identifying seven key ills of western capitalism examines the neglect of the relational underpinning of prosperity by the world’s two principal business titles – the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal.

They are the two giants of the global financial press.

One, acquired by Rupert Murdoch in 2007, is clearly of the Right. The Wall Street Journal has been a champion of the Republican tax cuts package that Donald Trump signed into law at the end of last year.

But if the WSJ can see no wrong in the signature project of the American Right, we need only cross the Atlantic where, in the outlook of the FT, we find a business newspaper that sees no good in the flagship enterprise of Britain’s Right – Brexit.

I exaggerate a little in saying “no wrong” and “no good” but only a little. Crucially, it’s the one-eyed character of both platforms on such consequential questions that is so striking and depressing.

First, America. The US Right and the Journal have signed up to an economic theory of tax cuts that has a status only one step higher than “written on the back of a cigarette paper”. The Laffer curve, infamously scrawled on to a bar napkin in 1974, purported to show that government revenues actually increased when certain tax rates were reduced – because of the turbo charge that they gave to the encouragement of initiative, overtime and other economy-expanding activities. But despite the four decades of evidence which suggest few tax cuts ever come close to financing themselves, the Republican Party has fallen irrationally in love with a theory that says there need be no conflict between an aspiration to be a tax-cutting conservative and a fiscal conservative. And it’s a deep love. Not one Republican law-maker in Washington has voted to raise tax in any meaningful vote since 1991.

As for team FT, they may have been a model of prudence when compared to the Journalistas on the topic of tax, but they can’t claim to be less ideologically rigid on the issue where their own journalistic qualities are being most tested. When it comes to understanding why more British citizens voted for Brexit than have ever voted for any other cause, party or candidate in the nation’s history, you might be interested to know that not one regular FT columnist is a Brexiteer. However, when he was interviewed for Radio 4’s Media Show, the newspaper’s Editor, Lionel Barber, insisted the FT mind was not a closed one. To prove this openness he named three pro-Leave writers who graced his OpEd pages but oh dear – it wasn’t much of a proof. For a start he named me – even though I’ve never written on the subject for them. Second was Iain Martin – who has been an exclusive columnist for The Times for 12 months. And, third, Jacob Rees-Mogg – but who doesn’t publish the Moggster these days?

We got closer to the FT‘s true attitude to the oh-so scandalous project of giving Britain the same self-determination that the vast majority of countries in the world enjoy (and most would never consider giving up) when a former Editor of The Economist wrote to the FT, saluting it for performing its “duty” of pouring scorn on the Brexit project. Bill Emmott’s dismissive was Tweeted as “letter of the day” by Mr Barber.

Curiously, we pay huge attention to the role of Fox News in corrupting American conservatism, and of the allegedly corrosive impact of the Daily Mail on British political discourse, but seem to have forgotten that the deadliest rot within movements and systems of thinking starts from the head. It’s not hard to discern whiffs of decay from within both the Journal and pink ‘un.

Surely any media organisations that failed to anticipate 2016’s unexpected shocks to the system, and which had been leading proponents of the policies that had helped to drive the political revolts, would be expected to have subsequently undertaken extensive soul-searching? But there have been few signs of it from either publication. If anything, they hold even more firmly to their former beliefs.

From a commercial point of view, neither the Journal or FT has much incentive to, for example, revisit immigration policies that provide rich readers and big company advertisers with cheap labour. Nor to question the property and monetary policies that have put rocket-boosters underneath the market wealth of the kind of people who buy jewelled Cartier collars for their dogs and splash out on the many other varieties of luxury goods sold from the pages of both papers’ glossy lifestyle supplements. For certain high-ups at the FT, 2016 will live long in the memory for a 65% jump in digital revenues from the paper’s How to Spend It magazine. What’s not to like about a year, and an economy, that delivers such largesse for the bottom line – directly from the 1%’s platinum cards?

Putting aside the commercial factors that inhibit honest rethinking, though, the key intellectual weakness that the FT and Journal share for the task of understanding our changing and anti-capitalist times is a lack of interest in the “unmeasured”. Just as tax relief for the family makes no sense to the Journal’s GDP-number-crunching-podcasters, so the behaviour of Brexit’s voters seems illogical to groupthinkers at the FT who, living in a world of day-to-day press deadlines and quarterly company results, can’t see much beyond the short-term economic costs associated with the uncertainty of transitioning from the stability of EU membership to a new, as yet unknown, arrangement.

Average citizens – and this is borne out by fascinating opinion polling – are less focused on the near-future. They, perhaps, can see the likelihood of an EU emerging that will make the weakness and drift of today’s Theresa May government seem trivial in comparison. They’ve made the simple but wise long-term bet that a 27-member organisation operating on 27 different electoral cycles will probably struggle to agree on anything much at all – especially anything important.

A greater degree of long-termism might not be the only thing Brexit voters could teach people who are willing to buy $67,000 necklaces. Three drivers of the votes of 2016 may be particularly deserving of more reflection.

Changes to family structure.

Family networks are fracturing. In part because rising house prices mean that many young families can’t afford to live near their parents. And what has been the consequences for this fracturing for the care of children and the elderly? Could it be that in wanting to put some limit on immigration and its effect on house prices – or at least by ensuring inflows become predictable – voters wanted to defend something that the FT and the economics profession never worries about in any meaningful way? What’s the economic value of your child’s gran being within walking distance? What has been the economic cost and implications for inequality of the wastelanding of so many working class family structures? And, fundamentally, what’s wrong with a society and an economics journalism that doesn’t seriously try to design housing or immigration policies that protect such relationships?

Security.

This may be the first and last time I ever quote Ted Cruz approvingly but I’d like to think the campaign commercial from his 2016 run (above) might have caused a few financial journalists to shift uneasily in their seats. Globalisation, immigration and sometimes doctrinaire free market trade policies have created huge amounts of insecurity for many poorer citizens of advanced nations. It’s easy for people unaffected (so far) by competition from Chinese manufacturers or Indian call centres to say insecurity is a price worth paying for cheaper consumer goods and services – when they are not paying that price.

The UK’s Vote Leave campaign “got it” in 2016 when it chose Take Control as its rallying call to people who felt increasingly “done to”. And another person who has “got it” is the economic historian Niall Ferguson. Talking to UnHerd, he argued that there had been inadequate political management of the pace of globalisation. While we might want to eventually end up in the same freely trading world that we are already largely immersed in, it might have been more judicious to have approached the destination more slowly and had the time to help victims of it to adjust more smoothly to competition.

And then there’s the nation itself.

The FT has its headquarters in London but most of its readers are international. They may appreciate their own territorial identities but probably not as much as the people that David Goodhart described as “Somewheres” – more rooted in their communities and with less wherewithal or interest to jet regularly to other places.

One of the greatest examples of national solidarity in modern times came when the Berlin Wall fell and the people of West Germany accepted a large tax hike to help pay for their fellow countrymen and women of East Germany to be fast-tracked through 40 years of economic falling behind.

When the people of Greece suffered austerity of a catastrophic kind from the euro crisis, did Germany offer similar solidarity or anything like it? No, despite the many ways in which the configuration of the single currency area has super-charged its manufacturing exporters. Exiting an artificial supranation in favour of something with so much more shared history, so many more shared institutions, and knitted together through familial interconnectedness wasn’t so dumb after all. This might well be proved during adversities in the years ahead – when Britain and/or the EU are called upon to make the kind of neighbour-respecting self-sacrifices that polities may depend upon to survive.

Adam Smith would not have made the same mistakes. He – through his own Moral Sentiments book and the overlaps of his thinking with that of Edmund ‘small platoons’ Burke – understood the importance of the non-material ties that bind.

But when the leading two newspapers of the business world are so indifferent to the social soils in which markets grow, it is no wonder that markets, market players and policy-makers can also become nine parts materialistic and only one part relational. They are obsessed with what the US commentator David Brooks has called resume values – values and decisions designed to power success in careers – rather than eulogy values – values and life choices of the kind honoured at a person’s funeral and in the remembering of the big, non-workplace choices they made for their families, neighbours and beliefs.

There is plenty that’s still brilliant in both of these newspaper titles. Unlike my colleague Douglas Murray, I wholly applaud the FT’s takedown of the President’s Club, for example. Saturday’s FT Magazine nearly always challenges and educates more than its rivals. Saturday is also the day when the WSJ shines. The Review section edited by Gary Rosen displays the intellectual curiosity that the daily comment pages no longer evidence very often. And, personally, I’ll never stop reading a paper which has the great Peggy Noonan on its books.

But, overall, mirroring the economics profession which has lost the humanitarianism of Adam Smith, the footloose multinational firms that have no community roots, the tech firms which see childhoods as easy routes to greater market penetration, and the executive company boards under pressure to hit quarterly performance numbers, there is little commitment within the pillars of the capitalist system to the people-sized institutions which civilise, educate and care, or to the national identities which people are likeliest to make sacrifices for.

It’s a shame that the newspapers that should be so well placed to challenge rootlessness within capitalism are actually so very far away from even reporting the necessity of doing so.

THIS SERIES CONTINUES TOMORROW.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe