Credit: Tama66, Pixabay

Given the parish systems of the Catholic and Anglican churches, the religious history of the United Kingdom means a church building is never far away. But are places of worship still needed in every community? And what do they offer today? We looked at multiple data sources to explore the extent to which religious buildings remain part of social life – and how.

Churches… are… closing. Or, where they are determined not to close but can’t sustain a sizeable congregation, they are grouped together with others and served by one clergy member across three or four churches – especially in rural areas where beautiful 12th century church buildings are sometimes used primarily for weddings with perhaps a monthly service to keep things ticking over.

That’s the story we often hear. But there are other stories too. The recently retired Bishop of London Richard Chartres was in post for more than 20 years (1995 until earlier this year) and not only refused to close a church in his patch, but introduced a programme of ‘church planting’: starting new churches in areas where church attendance is low.

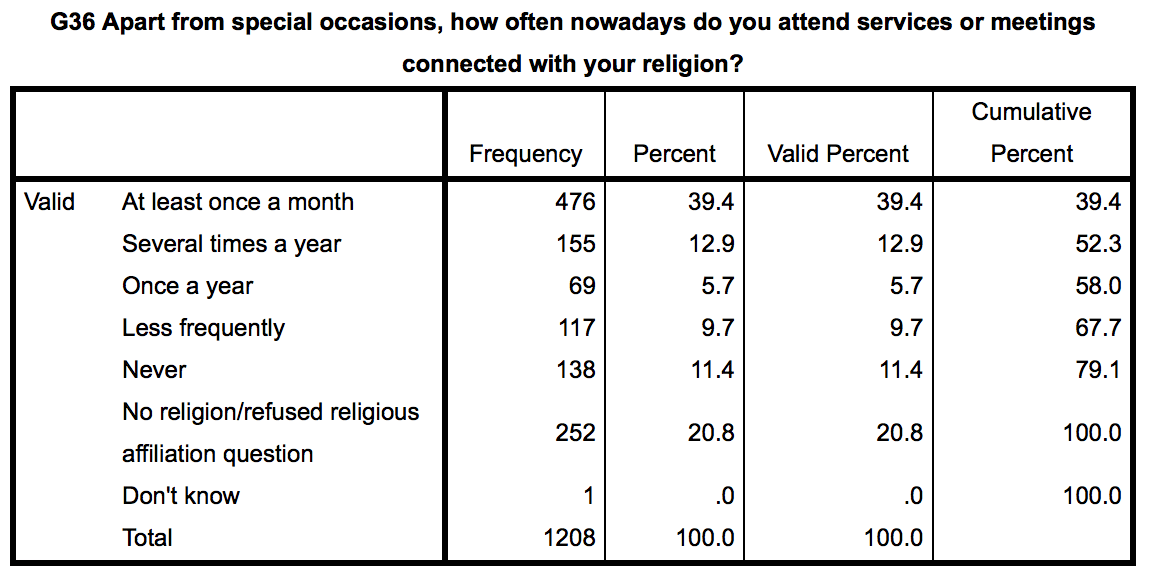

According to the British Social Attitudes survey, 22% of adults in Britain say they attend a religious service at least monthly – as do 39% of adults in Northern Ireland (please see tables at the bottom of this article). There is not a comprehensive list or credible statistic to calculate the total number of places of worship, not least because of their immense variety. Many new groups of worshippers begin by meeting in someone’s home or by renting a hall in a school and may not have a dedicated building for many years. According to the new Jewish Policy Research report on Synagogues in Britain, this is how Jewish worshipping communities have originated, as have many charismatic churches. Mosques are not always clearly visible from the street, if they are using a former disused building. At least not until Fridays when the line of people walking towards the place of worship indicates its purpose.

A communal gathering place remains part of millions of people’s religious practice, and draws in people from the local community and beyond in various ways:

Help in times of crisis: My UnHerd colleague Jonathan Aitken described the ways people from synagogues, mosques and churches leapt into action to help people evacuated from the dreadful fire at Grenfell Tower. Whether it’s churches sheltering terrified people fleeing rape and violence in Central African Republic, or mosques housing widows and children who fear attacks in Kashmir, some of the world’s most vulnerable people have found refuge in places of worship.

Solving local problems: According to the 2016 Cinnamon Network Faith Action Audit which collected evidence from 3,007 faith groups in the UK, each of those groups provided on average eight social action projects, managed 66 volunteers and had 1,696 interactions with people who needed help. Debt advice centres, parenting classes, lunch clubs for elderly people, youthwork, jobfinding schemes, and business start-up opportunities are offered in thousands of religious buildings around the UK. Cinnamon Network say their data suggests that this could equate to £3 billion worth of support for some of this country’s vulnerable people.

Our history and heritage: Our ComRes research for National Churches Trust earlier this year found that 83% of adults in Britain agree that the UK’s churches, chapels and meeting houses are an important part of our heritage and history. And, while Visit England’s latest statistics demonstrate a drop in tourist visits to some cathedrals which some people attribute to increased entry fees, it is still the case the millions of people each year visit or worship in a historic church building. There are some interesting surprises in our religious history. To find out what Charles Dickens had to say about the Mormons (yes, they were around in his time), call in to the Latter Day Saints visitor centre in London.

Awe and wonder: Styles of worship across all religions vary, and each has its denominations based on doctrine, worship and sometimes demographic[1. Denominations are present in all major religions and most minority religions. For example, chapter 2 of the recent Jewish Policy Research report into synagogue attendance in the UK carries a helpful list and analysis of the Jewish denominations in this country]. According to a new website to help people find a local Choral Evensong service, we’re flocking back to liturgical church services to hear choral music. Our research into use of six local case-study Church of England cathedrals for think tank Theos found that 92% of respondents said that their cathedral was a place where people can get in touch with the spiritual or the sacred.

LOOK AT THIS!

- Some of the world’s most beautiful places of worship – my favourite is the Taktsang Palphug Monastery in Bhutan

- The Guardian asked readers to send in photographs of empty places of worship

- Some of these before-and-after pictures of devastation in Syria include historically significant mosques

FURTHER BACKGROUND

…ON CHURCH ATTENDANCE

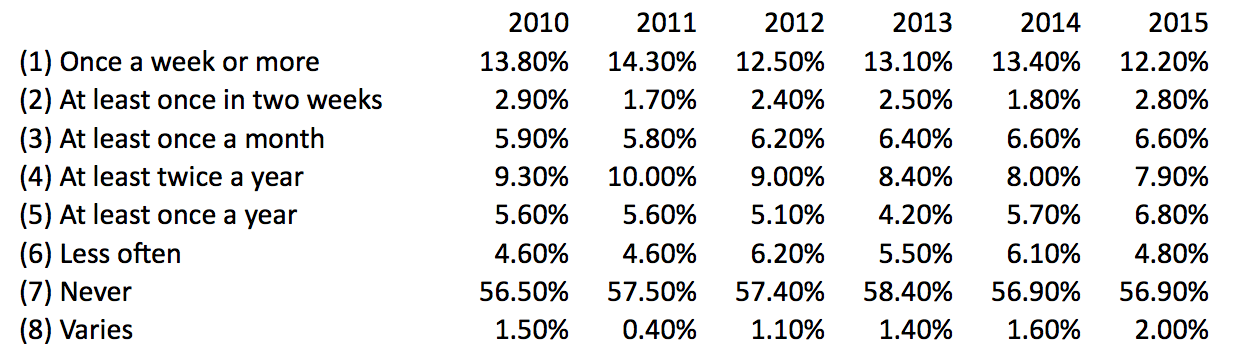

We downloaded data from the British Social Attitudes survey which showed responses to question about attendance at religious services;

Data supplied to us by the Life and Times survey in Northern Ireland;

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe